I vehemently dislike gratitude. One has to agree with Dostoevsky’s Father Zosima in The Brothers Karamazov:

The more I love mankind in general, the less I love human beings in particular, separately, that is, as individual persons. [...] To compensate for this, however, it has always happened that the more I have hated human beings in particular, the more ardent has become my love for mankind in general.

Much like loving, being grateful in the abstract suffers the same fate of vacuous sentimentalism. You can’t be grateful abstractly, no matter how many banal affirmations you parrot to yourself, because it isn’t real. To be grateful for everything is to be grateful for nothing. Besides, this world is a terrible place rife with unjust wars, poverty, inequality and unspeakable amounts of suffering, and so ethically speaking, abstract gratitude is a bête noire of mine. Indeed, the ethical act is to be ungrateful.

And yet, one can’t help but feel a deep sense of gratitude when it strikes you out of nowhere like an uncaused quantum-phenomenological event appearing ex nihilo. I’ve experienced this recently when reflecting on a book study of Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach (GEB) that I’ve been doing with

. So, the following piece results from an ungrateful person being struck by a particular instance of gratitude for a dear friend and fellow traveller, Shaye.Hofstadter is conceivably one of the finest synthesists of our time. His life’s work has been attempting to understand consciousness through a phenomenon he aptly calls Strange Loops. To be precise - studying consciousness begs the question: how do human beings with experience that undeniably have a subjective self, which we refer to as “You” or “I”, come to exist in a universe apparently made of meaningless unconscious objects like atoms or rocks? Or, in other words - what differentiates you from the phone you’re reading this piece on if we’re made of the same stuff?

Strange Loops are self-referential cyclical structures that let one find themselves back to where they started when moving through a given tangled hierarchy, meaning, there isn’t a well-defined highest or lowest level nor an objective starting or ending point. Of course, put so abstractly, this doesn’t tell much. But the strangeness of the loop emerges when seen in concrete instances across reality.

I will not deeply explain Strange Loops nor the ideas delineated in the book. If anything, by giving my intimations on its themes, I only hope this essay will evoke your curiosity to read GEB. It’s nonetheless worth mentioning that the book’s title itself directly points to Hofstadter’s characters of choice whose work he uses to elucidate his theories:

Gödel is pointing to the logician Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems (1931), which conclusively proved that all “sufficiently powerful” formally axiomatic systems, by virtue of their power, contain truths that are unprovable within a respective system. Moreover, as an extension of the previous proof, these systems cannot prove their own consistency. Mathematics, specifically number theory, is the eminent example of such a sufficiently powerful system making truth claims, i.e., 2 + 3 = 5, that cannot be proven within its axioms, inference rules and theorems, making it incomplete. This incompleteness, unfortunately, has to be seen through more jargonic terms: Gödel numbering systems, metalanguages and self-reference.

In the 20th-Century, Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell published the epochal Principia Mathematica (PM), which, among many, aimed at solving the antinomies like Russell’s Paradox that plagued logic, set theory and, by extension, the foundations of mathematics. In other words, they attempted to show conclusively that “2 plus 3 is indeed 5”, which, though you and I may think is obvious, isn’t the case once you get into the thick of things. In fact, we still don’t have absolute self-consistent proof for this statement. Despite PM’s ingenuity, it was mostly a lost cause—at least the part that attempted to foundationalise mathematics. And to make matters worse, Gödel enters the scene with a hunch to convert the ancient Epimenides paradox into mathematical logic (Epimenides was a Cretan who made the immortal statement: “All Cretans are liars.” Is he telling the truth?). Since PM claimed to be a complete system that grounded mathematics in symbolic logic—or at least was on its way to becoming one—Gödel took statements in PM and passed them through a Gödel function assigning a particular natural (or Gödel) number to each of them. As Prof. Joel David Hamkins explained, the simplest way to think of it is how programming languages humans understand are converted to machine code by compilers and interpreters to execute on your computer. While the form changes, the meaning remains. The Gödel numbering system does the same to formal systems. Afterwards, using these derived Gödelian numbers, he showed that metamathematical statements—statements about what each symbol in arithmetic formulas like “2 + 3 = 5” means—can be represented arithmetically through the same formulas. And here’s where the self-reference appears! Indeed, it’s strange because a truth statement makes claims about itself that, nonetheless, cannot be proven within the respective formal system through which the statement is formulated.

Let me try to re-articulate this colloquially in less formal language: Let’s say humans have created Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), supposedly reaching the singularity. This AGI will produce truths about reality that are unknown to us but are true because they’re provable within the AGI’s truth-generating system. In comes Kurt Gödel pushing the AGI to a corner and convincing it to say, “I will never say this statement is true.”—imagine this being similar to people convincing ChatGPT to say things they want except the AGI being omniscient (and hopefully benevolent) will never say untrue things. Now, the AGI recognises that it’s making a truth claim, which states it will not make such a claim, creating a paradox. And so this self-referencing paradox drives it into an existential crisis, and instead of doing anything else, the AGI decides to read Hegel for the rest of its life. Things only get worse afterwards.

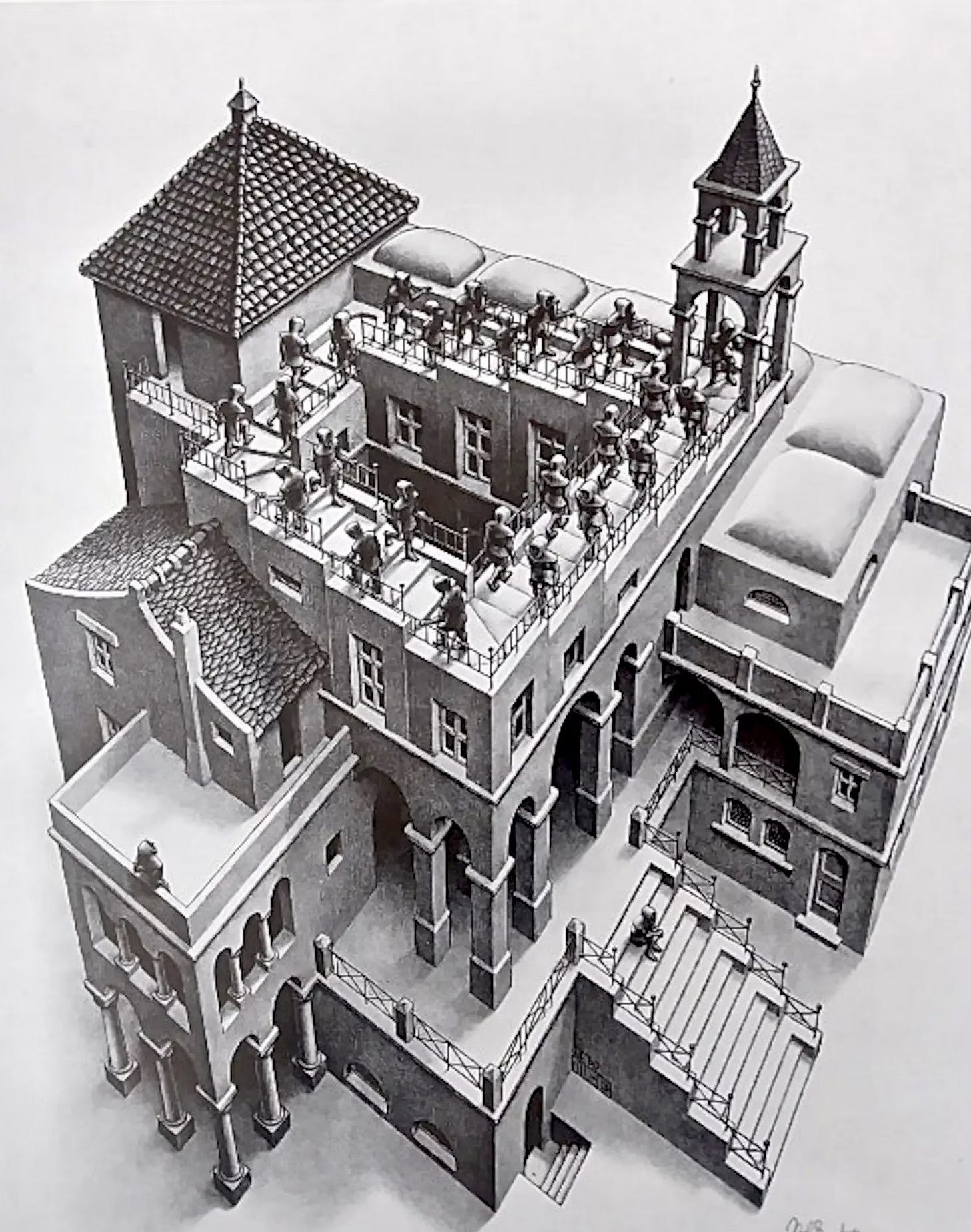

Escher is pointing to the works of the artist M. C. Escher, who created mathematically inspired art that notably brought to light mind-bending paradoxes. While Hofstadter has spared more than enough words in GEB to fastidiously explain how Strange Loops emerge in Escher’s work, I think it’s self-evident when you look at the pieces. So, I will not expound further but present a few of my favourite lithographs.

And these illustrate the hierarchical structure of the cyclical structure best.

Bach is pointing to Johann Sebastian Bach’s music. While being a casual enjoyer of Baroque music, I nonetheless have no understanding of music theory and needed Shaye’s help to make sense of how Strange Loops emerged in Bach’s compositions. The first time I listened to a rendition, I couldn’t pick apart anywhere a hierarchical cyclical structure occurred. But on seeing what’s being played visually, it’s obvious how Bach plays around with fugues in his melody. BWV 542 is one such piece that helped me:

In this fugue, you’ll see from the home note in which we start it keeps rising and returns back to the home note. When returning to the home note, you’d think the melody is concluded, but this “conclusion” ties into the beginning again of another fugue, resulting in a Strange Loop.

Hofstadter ultimately believes our conscious selves result from this ubiquitous Strange Loop phenomenon. He concludes I Am a Strange Loop, which succeeded GEB, claiming:

In the end, we self-perceiving, self-inventing, locked-in mirages are little miracles of self-reference. We believe in marbles that disintegrate when we search for them but that are as real as any genuine marble when we’re not looking for them. Our very nature is such as to prevent us from fully understanding its very nature. Poised midway between the unvisualizable cosmic vastness of curved spacetime and the dubious, shadowy flickerings of charged quanta, we human beings, more like rainbows and mirages than like raindrops or boulders, are unpredictable self-writing poems—vague, metaphorical, ambiguous, and sometimes exceedingly beautiful. (p. 363)

Forgive me for the cliché, but once you apprehend the concept, you can’t help but see it everywhere, perhaps including in yourself. Or, to use the term Shaye loves, you begin to see isomorphism across the world, within and without.

Hofstadter and Germans Idealism

In the isomorphism-istic spirit, I can’t help but mention a peculiar similarity between Hofstadter’s and the 18th-century German Idealist philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s work. Unsurprisingly, it’s another eminent synthesist of our time (in my view, the pre-eminent one), Slavoj Žižek, who noticed this resemblance. Yet again, I will not expound on Žižek’s analysis and subsequent critique of Hofstadter’s work but only lay down a few elementary points that piqued my interest. For a detailed exposition, read Interlude 6: Cognitivism and the Loop of Self-Positing in his magnum opus Less Than Nothing.

A heads-up: the following excerpts are highly speculative, and unfortunately, you’ll need a lot of philosophical (and historical) context to understand the nuances.

In Fichte’s Wissenschaftslehre, he develops his ontology of the subject (effectively, think of this as self-consciousness) as being a self-positing “I” where the subject is the result of posting itself and having been posited much like a self-referential loop. The “I” exists purely for its own sake and is the result of this process that asserts and finds its beinghood off its assertion; there’s nothing substantial behind the ‘self-positing “I”’. We could call this radical subjectivism. As Žižek writes, juxtaposing Fichte with Kant:

Fichte allows us to clarify this confusion which arises when we insist on the opposition between the noumenal and the phenomenal: the I is not a noumenal substance, but the pure spontaneity of self-positing; this is why its self-limitation does not need a transcendent God who manipulates our terrestrial situation (limiting our knowledge) in order to foster our moral growth—one can deduce the subject’s limitation in a totally immanent way. (Less Than Nothing, p. 163)

Around 1800, Fichte engaged in a closer and very refined analysis of the I’s self-positing, and arrived at a further surprising result, a kind of “splitting the atom” of the absolute I’s self-positing: he discovered that the most elementary structure of self-consciousness—the I’s self-positing—is more complex than it initially appears, and displays a precise structure. Fichte’s starting point is that the Self is not a product of some pre-subjective activity that generates it—the Self comes immediately with the activity. (Ibid., p. 181)

In GEB, as we saw above, Hofstadter asserts that we’re nothing more than a self-relating phenomenon emergent in the universe, which Žižek dedicates a whole section to critiquing:

Let us begin with some strange echoes between cognitivism and German Idealism. Does not the title of Douglas Hofstadter’s book on the paradoxes of (self-)consciousness, I Am a Strange Loop, best capture Fichte’s early thought? Hofstadter understands his work as a contribution to the “self-referentialist” theory of consciousness-the underlying idea is not a simple “reductionist” neurological materialism (a search for the material-neuronal substrate of consciousness), but a much more interesting one: independently of its material (neuronal) support, a certain abstract-formal paradoxical structure of self-referentiality at the level of thinking itself is constitutive of consciousness. (Ibid.,p. 717)

The development of Hofstadter’s argument culminates in his claim that consciousness is an epiphenomenal grand illusion and the subjective Self or the “I” doesn’t exist:

… an epiphenomenon could be said to be a large-scale illusion created by the collusion of many small and indisputably non-illusory events. (I Am a Strange Loop, p. 93)

... And this is Žižek’s criticism of the Strange Loop hypothesis apropos consciousness. Hofstadter, much like the majority of cognitive scientists, linguists, physicists, and generally any analytical philosophy-inspired theorist, is a Kantian. They believe reality has a substance that’s always out of reach for our phenomenal self. Although even calling it a substance would be inaccurate as this “thing-in-itself” (German: Ding an sich) is the noumenal aspect of reality that we cannot cognise, experience empirically or otherwise, and consequently not speak off, yet exists. Indeed, for Kant, all of what we colloquially call “the world out there”, including spacetime, was a quasi-illusion1 where cognitive structures in our mind mapped with the objective world outside of our subjective self. Kant specifically saw our inability to grasp reality, only experiencing it within a “transcendental horizon,” as a limitation of ourselves and not objective reality. Thus, he left a gap in our knowledge of what exists, an epistemological barrier between us and the world.

Herein comes Žižek’s Hegelianism and questions the presuppositions Kantians like Hofstadter hold to posit the “illusions of ourselves.” For them to deduce the illusionist theory, they presuppose reality is ontologically complete: the world is substantially placed as it is already determined and closed off from a future or a past where, despite for our subjective selves, phenomena seem arbitrary and even quantum events are indeterministic or at least probabilistic the cosmos is fundamentally a static, eternal, unchanging block with set schematic rules. In theological terms, if a Kantian is asked, does God change his mind? The answer would be a resolute no. Through such an epistemic framework, post-Kantian theorists arrive at the myriad Hofstadterian views, be it the tangled hierarchy of consciousness or Daniel Dennett’s compatibilism hypothesis of free will. But the Žižekian-German Idealist question to them is why tacitly assume we’re outside of reality? Instead of asking what allows our minds to experience the world, invert the inquiry: what kind of reality allows experiencing subjects like us to emerge?

Even if our experience was an illusion, this illusion has an ontic status in reality, and it cannot be dismissed as an epiphenomena; despite the “epi-” it nonetheless is still a phenomenon. By critiquing the Buddhist discourse, which, in agreement with David Hume, claims the Self, understood as the “I”, is an illusion and indeed that nothing exists to the “Self” but a void, Žižek speculates that this Nothing is what truly exists:

The proper Kantian answer to Hume’s argument against the Self (when I look into myself, I see a multitude of particular affects, notions, etc., but I never find a “Self” as an object of my perception) is a kind of Rabinovitch joke: “When you look into yourself, you can discover your Self’ “But I see no Self there, there is nothing in me beyond the multiplicity of representations!” “Well, the subject is precisely this Nothing!” The limitation of Buddhism is that it is not able to accomplish this second step-it remains stuck at the insight that “there is no true Self’ All the German Idealists insist on this point: while Kant just leaves it empty (as the transcendental Ego-the inaccessible Thing), Fichte endlessly emphasizes that the I is not a thing, but purely processual, only a process of its appearing-to-itself; Hegel does the same.” (Less Than Nothing, p. 720)

Since Fichte sees the Self as a process, the so-called illusion of the Self is what gives it an actual ontological status. The Nothing is not that which inexists but a positively charged Nothing:

“In a way, Fichte says the same thing when he claims that the I exists only for the I, that mental representation exists only for the mental representation, that it has no “objective” existence external to this loop. So when Hofstadter defines (self-)consciousness as a hallucination perceived by a hallucination, he is here not “too radical;” pushing things towards a paradox unacceptable to our common sense, but not radical enough: what he does not see (and what Fichte clearly saw), is that the paradoxical redoubling of hallucination (a hallucination itself perceived by a hallucination, that is by a hallucinatory entity) cancels (sublates) itself, generating a new reality of its own. (Ibid.,p. 722)

… while what the observer immediately identifies with in the experience of self-awareness is a fiction, something with no positive ontological status, his very activity of observing is a positive ontological fact. Metzinger's (and Hofstadter's) solution is to distinguish between the reality of the observing process (there is no “observer” as an autonomous Self, just the asubjective neuronal process) and the "transparent" (self-)perception of the agent of this process as a Self. In other words, the distinction between appearance (of phenomenal “transparent” reality) and reality in transposed into the perceiving process itself. (Ibid.,p. 723)

I also feel obligated to mention Žižek’s emphasis that the other is necessary for the Self to become actual, not merely ethically but ontologically. That is, we find ourselves through other people.

... when Hofstadter defines the Self not as a substantial thing, but as a higher-level pattern which can flow between a multitude of material instantiations, he is not consistent enough and repeats the mistake of the brain-in-the-vat fantasy: the “pattern” which forms my Self is not only the pattern of self-referential loops in my brain, but the much larger pattern of interactions between my brain-and-body and its entire material, institutional, and symbolic context. What makes me “my-Self” is the way I relate to the people, things, and processes around me-and this is what by definition would be lost if only my brain-pattern were transposed from my brain here on Earth to another brain on Mars: this other Self would definitely not be me, since it would be deprived of the complex social network which makes me my-Self. (Ibid., p. 727)

I understand Kantians would vehemently oppose my characterisation of Immanuel Kant as an idealist or, even worse, a New Age solipsist leading to a Maya ontology, as his philosophical project was antithetical to such worldviews. I, however, did make intimations mostly to provoke and radicalise Kant’s transcendental horizon only for us to move beyond Kantianism to German Idealism and Whiteheadeanism, crossing the threshold, as Matthew David Segall would’ve put it.