Guiding Axiom’s

The following is the fifth guiding axiom for this newsletter, The Unhappy Man. It’s one of many that I hope to share in the upcoming weeks.

Any Kierkegaardian is familiar with that captivating admission in Either/Or (P. 38), “My melancholy is the most faithful mistress I have known; what wonder, then, that I love her in return.” Most of us of the existentialist ilk have fully bought into the dogma of the depressed yet perspicacious philosopher. For us, all great truths lack profundity if not written in a Schopenhauerian pessimism about our condition; the misery of existence is what those with great intelligence and deep hearts have come to see; to not see this verity is nothing but naivety. At least, this is the bullshit we tell ourselves.

To be depressed or suffer needlessly is far from the romantic beauty we give to it. None of it makes one’s soul deeper and inspires philosophically penetrating poetry or Dostoyevskian literature. In fact, when I read my nonsensical journaling, written during the low points, I see it as nothing but vain, egotistical pabulum—which is why I stopped journaling; it’s a waste of time and better drinking away your sorrows1. But beyond ostentatious vanity, we all dwell in our misery purely to feel something. We often deliberately seek pathological relationships only because the melodramatic pain of love reminds us of our humanness; better to feel pain than nothing at all. Or, as Dostoevsky wrote, “If he [human beings] does not find means he will contrive destruction and chaos, will contrive sufferings of all sorts, only to gain his point!” (Notes from Underground, C. VIII) And, of course, being willing to suffer through love, particularly romantic, tells us of our goodness, of our higher virtues in being authentically self-sacrificial for another. Such is why Nietzsche wrote, “ultimately, it is the desire, not the desired, that we love.” (Beyond Good and Evil, A. 175) I must admit that I’m ashamed of how pathetic we are as a species.

Having said that, I see why modern people lust after suffering as we’re given the impossible choice of contrived pseudo-happiness in the form of New Age self-help which we all know is rife with empty platitudes, i.e. Bullshit, and the finger-wagging “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” heartless, American stoicism; it seems we’re stuck in this binary. The modern age is an era of nihilism, so as Nietzsche, the man who explored the symptom to its ultimate, wrote:

“Read from a distant planet, the majuscule script [Majuskel-Schrift] of our earthly existence would perhaps seduce the reader to the conclusion that the earth was the ascetic planet par excellence, an outpost of discontented, arrogant and nasty creatures who harboured a deep disgust for themselves, for the world, for all life and hurt themselves as much as possible out of pleasure in hurting: – probably their only pleasure.” (On the Genealogy of Morality, P. 85)

The passage above is from his scathing critique of the ascetic ideal. This mode of life he pillories has little to do with religious asceticism, per se, but rather a cultural zeitgeist—despite the characteristic phenomenon being cross-cultural. For instance, he would be as equally contemptuous of the contemporary Postmodern Stoicism of the Ryan Holiday types or Neoliberal Western Buddhism that turns a blind eye to the problems of the world and decides to inflict suffering on oneself for the “pleasure” it evokes, i.e., cold showers, fasting, CrossFit, etc. Irrespective of religious connotations, all such modes of being manifest a drive towards the ascetic ideal. So his sentiments are apt to any pseudo-suffering we create purely to inject artificial meaning into our barren, desolate veins. Whether in the form of modern self-help cults with their unending self-flagellation or a morbid romantic relationship that’s conspicuously making everyone suffer, we desire meaning! Perhaps the intrinsic human reality is meaninglessness and the incompleteness of life. Therefore we ought to be cognisant of how we respond to our predicament, and one can only live authentically once this datum is confronted. In my view, the only true antidote to meaninglessness or the nihilism of our culture is love; but that’s a whole other essay (or book).

Personal Suffering

On suffering as a psychological phenomenon, I find affinity with the Žižekian sentiments2 on the matter: pleasure never satiates us as there’s only so much of it one can enjoy; therefore, we seek the pleasure beyond pleasure and willfully suffer for an ostensibly nobler cause. But in reality, this is our yearning to fill the void in life; we hope to overcome the abyss with a deeper spiritual meaning—sometimes with a touch of romanticism as we see in fascism—that’s elusive for us in the technological age3 where to Dostoevsky’s dismay man has become “nothing but a piano-key.” (Ibid. VIII) Martyrdom, for instance, typifies this drive within us. Despite the word’s etymology, a martyr is not a purely religious individual or some fundamentalist fanatic. To a certain extent, everyone sees themselves as a martyr, from a self-sacrificial parent, an assiduous employee working fifteen hours a day at a trendy postmodern start-up to a nurse working in palliative care. To the martyr in us, the pain of sacrifice and duty gives us that pleasure4 when the so-called worldly pleasures (generally, a derided term, but it shouldn’t be) are inadequate. Or as G.K. Chesterton wrote, “Pessimism is not in being tired of evil but in being tired of good. Despair does not lie in being weary of suffering, but in being weary of joy.” (The Everlasting Man, P. 97-98)

Of course, none of this implies we shouldn’t take upon actual responsibility in life and carry the world’s burdens. Nor does it mean, above all, that love is free of a sword and fire: Alain Badiou observed that our culture is atypical in trying to sell a “safety-first concept of ‘love’. It is love comprehensively insured against all risks: you will have love, but will have assessed the prospective relationship so thoroughly, will have selected your partner so carefully by searching online - by obtaining, of course, a photo, details of his or her tastes, date of birth, horoscope sign, etc. - and putting it all in the mix you can tell yourself: ‘This is a risk-free option!’” But he fights back against such safetyism: “I am convinced that love cannot be a gift given on the basis of a complete lack of risk. The Meetic [French online dating service] approach reminds me of the propaganda of the American army when promoting the idea of ‘smart’ bombs and ‘zero dead’ wars.” (In Praise of Love, P. 5-8) So we ought to pick our battles and be cognisant of the difference between sacrifice for higher, life-sustaining ideals of love, justice, etc., that bring forth genuine good, and on the other hand, suffering for the love of suffering itself; the latter is nothing but vanity and exhibitionism. Any blind renunciation of pleasure and seeking of suffering becomes a kind of machiavellian narcissism worse than what you’d see from a typical, and more explicit, “Trump-like” narcissist, as the former is the ultimate wolf in sheep’s clothing. Ergo, as Žižek candidly tells us, “Never fall in love with your suffering.”

Suffering As A Category

But I’d go a step further and assert never fall in love with suffering as a category, period. Firstly, because it’s simply unpragmatic, suffering doesn’t make anyone’s life better and has no ennobling qualities in itself. Secondly and more importantly, the fixation on suffering has imbued unspeakable amounts of evil. Case in point: I’m disgusted by how postmodern neoliberals (that’s most of us) fetishise poverty. We implicitly believe there’s some deep-found wisdom in the suffering of the poor, that those exploited in the Mica mines in India for extortionate makeup products have a profundity to their souls that we degenerate Westerners have lost. Or we would salivatingly cite an outdated statistic about Bangladeshi people being happier5 than rich Americans. But isn’t all of this romanticisation of poverty utter nonsense? Isn’t it yet another example of the aforementioned suffering fetish, this time despicably manifested in the political domain? I doubt any of us unpretentiously listen to a poor person except through an ideological lens, which tells us what to hear over what the person’s truly saying. Personally, whenever I’ve spoken to someone struggling to survive and barely making ends meet, I see nothing but despondency, pain and resentment; not the pristine goodness in the souls of poor folk we’d prescribe on them; not the wisdom of the heart we’d read about in a Charles Dickens novel—of course, Dickens knew this better than all of us.

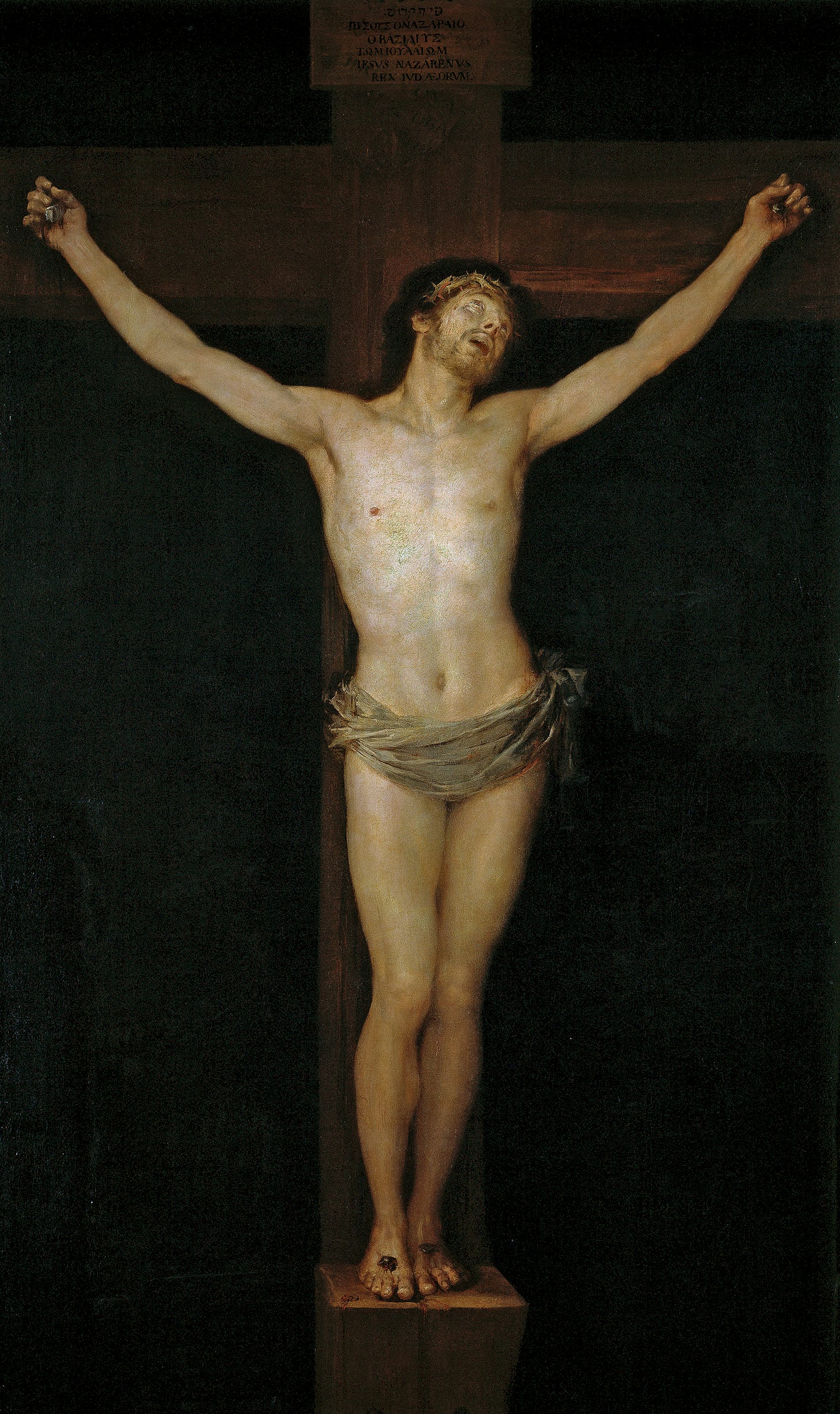

I partially blame the misappropriation of the crucifixion for the fetishism of suffering. And I’m not surprised! As someone deeply enamoured by Christ, the crucifixion is an infinite supra-historical event happening in the eternal now6—meditating on it has changed my life (or, more accurately, given me a new one), and I shall expound on the matter in later essays. In any case, crucified Christ is only part of the Christian narrative, and we replace the whole with a fragment at great peril; we ought to never forget Christ also resurrected, as bizarre as that sounds. Notwithstanding one’s religious beliefs, be it theist, atheist, or “spiritual but not religious”, all of us think of ourselves as a suffering Christ7, carrying a cross. Because as Don Cupitt wrote, “Nobody in the West can be wholly non-Christian. You may call yourself non-Christian, but the dreams you dream are still Christian dreams.” Since we, even migrants to the West like myself, “dream” in Christianity, we ought to never rush into glamorising the suffering Christ and instead be searingly sceptical of our underlying humanistic intentions behind the veneer of self-sacrificial love.

Perhaps Christ was thinking my dad’s a malevolent and sadomasochistic son of a bitch who’s thrown me into gratuitous suffering because of a twisted cosmic jurisprudential atonement he’s conjured up ex nihilo—at least this is what theologians like William Lane Craig tell us. If Christ indeed was the God-man, then for him to say “Eli Eli Lama Sabachthani?” (“My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?”, Matthew 27:46) is an unsurprising remark for one to make while being crucified. And here, as Žižek points out, momentarily, God himself becomes an atheist—it’s the negation and evident hatred of God (e.g. Book of Job) that makes Christianity unique from any other religion8, and makes our culture outlandish. We see in Christianity the utmost palpable story of existence: human suffering can be so unbearable that even God, once he comes down to us, realises he cannot bear it and loses faith; ergo, the “separation from God is a part of divinity itself.” And it’s only the Christian God that knows the alienation of being human.

I go on these detours only to explicate my view that suffering in itself has no higher, soul-maturing virtue. We don’t have to artificially create and fetishise it, as pain, tragedy, and unhappiness are already concomitant with the vicissitudes of life. So despite this newsletter being called The Unhappy Man, I shall never fall in love with unhappiness and suffering; if I ever do, I will stop writing.

This is a joke.

Influenced by Jacques Lacan's concept of jouissance and the Freudian death drive, Žižek’s made the following point in his books and lectures [paraphrasing], “Don’t fall in love with your suffering. Never presume that your suffering is in itself proof of your authenticity. Renunciation of pleasure can easily turn into pleasure of renunciation itself.”

Read The Question Concerning Technology Essay by Martin Heidegger to understand what this age entails.

Pleasure, which could be misunderstood by how it’s colloquially used in the carnal hedonic sense, may not be the aptest term for this instance, but I’ve decided to stick with it since I’m speaking in Freudian nomenclature.

Who says happiness is the purpose of life? Or that it’s even something worth measuring? It doesn’t matter that they’re happier if the rapacious fashion industry allows for tragedies like the Rana Plaza Collapse. In such moments, happiness is an unethical category; it’s out of the question.

I borrow this term from Paul Tillich’s book, The Eternal Now, which encapsulates most of his superlative theology.

To understand why, I recommend starting with Tom Holland’s Dominion and Slavoj Žižek’s Fragile Absolute.

Martin Scorsese’s Silence (2016) explores this phenomenon well with a modern flavour of man’s helpless frustration at God. And G. K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy encapsulates this idea best from any modern theology I’ve read.