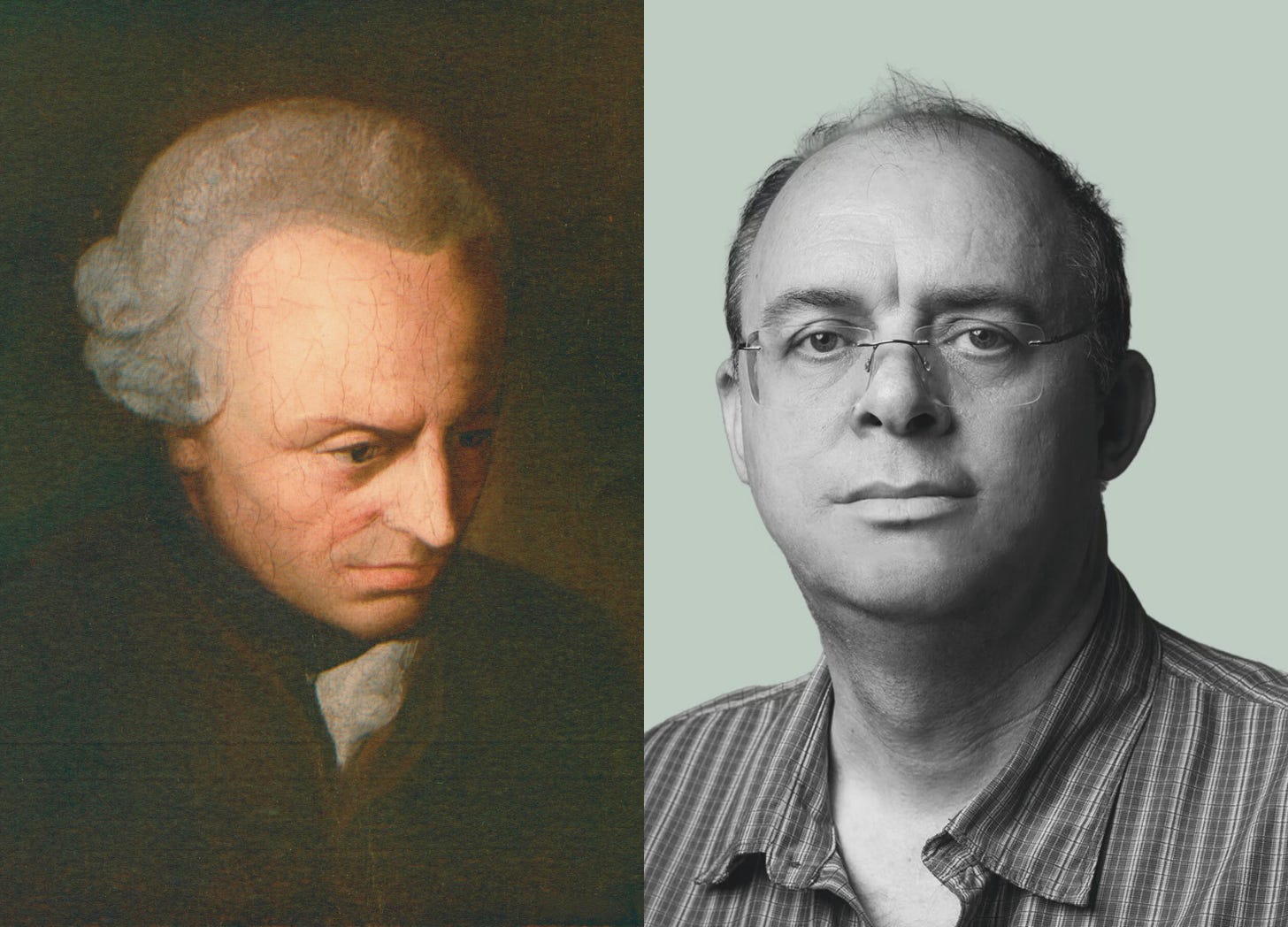

Is Kant the Enemy of Metaphysics?

A Conversation With Graham Harman and Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO)

“Why is there only one possible exit from modern philosophy? Because modern philosophy lives and breathes from a single basic principle: the notion that thought and world are the two poles of the universe, the first of them immediate and radically certain, the latter less certain but impressively masterable by science.” (Harman, 2020, p. 143)

— Graham Harman

An editor’s note:

Dear reader,

The following is an edited transcript of an interview I did with Graham Harman. While Kant was the main topic of discussion, we also touched on Schelling, Merleau-Ponty and the philosophy of time in OOO. If these interest you and you prefer listening to reading, you can find Harman’s episode on my podcast through YouTube, Spotify, and other platforms.

Alfred North Whitehead famously said, “The safest general characterisation of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” And in this vein, Slavoj Žižek1, characteristic of his provocative MO, remarked that all philosophy progresses by being against a thinker: Every philosophical epoch is defined through a critique of a giant, be it Plato, Descartes or Hegel. That being said, Kant, I find, plays a peculiar role; he truly created a rift in modern philosophy. There are those who can’t stand him and fault him for many of the problems we face in philosophy; this is a diverse camp with varying thinkers as different as the philosopher of physics Tim Maudlin, spanning to the speculative realist Quentin Meillassoux, inaugurated by his best-known essay After Finitude. On the other hand, one may argue the whole of the analytic philosophy tradition and, albeit radically differently, thinkers like Martin Heidegger2 are neo-Kantians and indeed see Kant’s rupturing of metaphysics with his transcendental philosophy to be the ‘Copernican Revolution.’ In other words, there’s no middle ground with Kant; either you think he is where the problem in contemporary philosophy started, or you are a card-carrying Kantian, claiming he’s the most important philosopher since at least Plato.

Graham Harman, broadly speaking, could be put in an anti-Kantian camp, but perhaps the ‘time-to-get-over-Kantianism’ camp would be a more apt one. He holds Kant responsible for the splitting of philosophy, a split resuting in an unintentional deflation of metaphysics, i.e., nowadays if people wants to know about fundamental reality, questions of beginning and end, infinity and finitude or freedom and determinism they go to a physicist or biologist for answers not a metaphysician—notwistanding the zeitgeist beginning to shift in the past few decades as science faces unassailable paradoxes and at least the acute scientists are knocking on the philosophers door for help. Harman’s contention is that the ‘cutting up’ of the world by transcendental idealism, whether this was Kant’s intention or not, created an “onto-taxonomy” for modern philosophy in which the two major poles of reality are “thought” and the “world.” This post-Cartesian assumption, Harman believes, is wrong.

.

A conversation from Dec 15, 2024:

Rahul Samaranayake: … This is the perfect segue to get into the topic of the big bad guy: Kant. You’ve said before that the reason science has a ‘monopoly on reality,’ so to speak, is because, after Kant, in many ways, philosophy can’t talk of objects independent of the subject. And so, given we sort of discussed your paper, The Only Exit from Modern Philosophy, let me ask a very fundamental question: Is Kant the enemy of metaphysics?

Graham Harman: No. I think we have to focus on the positive in Kant, and ironically, that positive is the part that everyone wants to forget; namely, the ‘thing-in-itself.’ It’s the strangest thing that Kant, undoubtedly the most influential philosopher since Plato and Aristotle, launched his revolution with the notion of the thing-in-itself, and yet has itself come to be interpreted as a form of dogmatism. I get a lot of critiques of my philosophy that are essentially critiques of the thing-in-itself. People forget that the thing-in-itself is what prevents dogmatic metaphysics from working.

RS: He was trying to save metaphysics from dogmatism, right?

GH: Yeah! And it’s not possible in its dogmatic form, but the way you stop dogma is with the thing-in-itself. The thing-in-itself is not a piece of dogma. That’s a German idealist addition; this idea that the things-in-themselves are themselves contradictory and therefore a residual piece of dogmatism. On the contrary, the finitude of cognition is Kant’s central breakthrough, and that is the thing-in-itself that allows them to do that. Now, the mistake that’s made is that people—and not just people Kant himself did this—also attached that too readily to the other part of the Kantian package, which is that therefore the proper role of philosophy is simply to critique the transcendental conditions of access to reality. Because we are humans and therefore we only have access in human experience to ‘human stuff,’ we do not have access to what goes on in nature, and therefore we cannot talk about it; that would be dogmatism. But there’s an equivocation here, I think. Dogmatism means trying to talk about a thing as though we’ve had direct access to its properties, as though the thing were directly present before us and could be exhaustively described. It’s not dogmatism if you talk about something that’s not you as long as you’re aware that it too is something you can’t talk about in terms of all of its properties being exhausted. So the critique of dogmatism means that I cannot prove using reason that God exists for Kant, but it doesn’t mean that I can’t talk about what happens metaphysically when two dinosaurs are fighting, or when fire burns cotton, the famous Islamic example from the Middle Ages. And there’s an odd tendency to make a Kantian-flavoured response that you can’t talk about fire burning cotton because that’s outside of human experience, you’d be dogmatic if you’re talking about it. No, you wouldn’t—you can talk about fire burning cotton just as readily as you can talk about your own mind because, as mentioned in our reflections on psychoanalysis, we don’t have any more direct access to our own minds than we do to fire burning cotton. So those are on the same level; they are both equally valid topics of philosophy: introspection is not any more readily accessible to us than physical causation.

Now the second defense mechanism kicks in here and people say yeah but science already does that and are you going to tell science what to do when it comes to fire you’re going to end up with a crazy metaphysics of nature like Schelling aren’t we past that… haha, okay, but again that assumes that the natural sciences are telling us everything we need or can know about inanimate objects. Yes, scientific theorising is the best we can do when it comes to mathematised spatio-temporal descriptions of how certain physical things interact when they come together, but that’s not the only thing going on when two objects interact because as mentioned, objects contain subcomponents they are emergent in some way in which interactions take place at all of those levels and boiling them all down to the language of physics isn’t necessarily going to get you all of those; in fact we know it isn’t. And then another defence mechanism that kicks in is people say ‘Okay, then tell me how object-oriented ontology is going to help physics?’, which again begs the question, it’s saying that unless something cashes out in the results of physics, it’s worthless when it comes to inanimate nature. So the answer is possibly object-oriented ontology will contribute nothing to physics, or another possible answer is that in 40 years it’s very relevant for physics that some of the concepts of ontology could be picked up by physics, just like some of Kant’s, Leibniz’s, and Mach’s were. Physicists have always known this, at least until the Anglophone anti-intellectual scientism of the postwar era; Feynman is sometimes accused of this, and Hawking deserves a bit of it. Whereas the continental European physicists always had a bit more of a reflective, empirical, and theoretical side, you’ve got Bohr reading Kierkegaard and Einstein reading all kinds of stuff from the history of philosophy. So we shouldn’t be intimidated by the anti-philosophy attitudes of the Feynmans and the Hawkings, and even in Feynman’s case, it isn’t that clear.

There is a lot of stuff out there that physics is not the right medium to discuss and this is very clear in the case of aesthetics, I’ve mentioned it in the case of law, and so we can celebrate the greatness of physics; modern physics is certainly one of the greatest human achievements of all time, the things that it’s opened up and also the perils opened up but that does not mean we should all bow down and say how may I serve thee master which is unfortunately how many analytic philosophers behave towards the scientists. So, that’s the first thing that needs to happen: people need to accept that there are many fruitful discourses about the world that are not necessarily scientific in the usual sense. The other thing, of course, they have to accept is that we do not have direct introspective knowledge, that’s more of a statement aimed at the transcendental idealist philosopher types, they ought to study a little more psychoanalysis and see how opaque our introspection really is and how mediated it is. Then we’re going to see that the two polls of the Kantian division of labour don’t necessarily work that well. And in a sense, OOO is a Kantianism, it’s just a Kantianism that isn’t just about the human subject, it’s one in which finitude and the thing-in-itself also infiltrate inanimate interactions. And that’s what I think’s new about OOO in the philosophical story.

You have Whitehead placing all causal relations on the same footing as perceptual immediacy. But Whitehead is a thorough relationist in his ontology. Hence, he thinks the objects are nothing more than their relations. In contrast, OOO is saying the opposite, that there’s a surplus in these relations and that these relations are just as tragically doomed as the human romantics’ failure to grasp the meaning of a ruined temple; the same thing happens at the inanimate level.

RS: You’ve put it succinctly in that article.

The only way to escape this assumption, the only exit from modern philosophy, is to cease conceiving of the thing-in-itself as something “unknowable to humans,” and to reconceive it as the excess in things beyond any of their relations to each other. (Harman, 2020, p. 139)

RS: I thought that was beautifully put.

GH: Thanks, I couldn’t have said it better myself, haha!

.

RS: The question of appearance… I remember reading about this a while back in reading Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything (2018). Now, of course, Hegelians also reject the thing-in-itself, and they even claim that the essence is split in itself, which is why they appear to us, so to speak. And so does OOO also reject the thing-in-itself, or do you reconceive it?

GH: I accept the thing-in-itself because there is no commensurability between the thing and any causal effect of the thing. In other words, a thing and the version of that thing that anything interacts with are not going to be identical, e.g., when a fire burns a cotton ball obviously countless features of that cotton ball are completely irrelevant to the fire’s interaction with it, and yet those qualities are to some extent part of the cotton, it’s just that no entity is equipped to interact with all of the qualities of another entity. And this is also incidentally why I reject the concept of matter. I think the entire reason the concept of matter exists in the history of philosophy is to provide an alibi for how one thing can move into another without changing, specifically in classical model of knowledge, i.e., supposedly, when I know a horse, the form of the horse comes into my mind but the matter of the horse obviously does not, or else I have a giant horse in my head, okay… but what if there is no such substratum called matter that’s able to to hold this horse form in it so that the only difference between the horse in reality and the horse of my mind is that one is in matter and the other is not. No one’s ever seen this matter; all we’ve ever seen are forms, all we’ve ever detected are forms, we’ve never detected formless matter, and I think a better model of knowledge is that the form is transferred. It’s like transmitting communications down the line: there’s going to be some noise, some distortion, some signal loss and this is how knowledge works as well; it might not all be loss, it might also be enhancements, it might be that humans are able to see more in a thing than is actually there, for instance, but knowledge is a form of translation. This is why I consider humans to be translating animals rather than critical animals; we’re able to bring vastly different things together into the same medium, and obviously, economics is one of the more controversial manifestations of this case. You put a price on everything; that’s the most extreme example of bringing all heterogeneous things together under one yoke, but that’s an essential tendency in human beings. We might need to control it in certain ways, but that’s who we are, that’s what we do. We put things under a single yoke, we believe in more, and we link more. So there’s grounds for a new anthropology, a new philosophical anthropology.

RS: Yes, I’ve got another good provocation.

OOO holds with Latour that there is no transport without transformation. A form does not move–whether from the thing to the mind or in any other manner–without undergoing some sort of translation. In this age of resurgent materialism, we need less materialism and more formalism. (Harman, 2020, p. 144)

References

Heidegger, M. (1997). Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics. Indiana University Press.

Harman, Graham. “The Only Exit from Modern Philosophy.” Open Philosophy, vol. 3, no. 1, 24 Mar. 2020, pp. 132–146, https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2020-0009. Accessed 28 May 2021.

He said this in an interview, but I’ve forgotten the source. You may just have to trust me on this one.

I know Heidegger’s relationship with Kantianism is controversial. But at least it’s clear to me that Heidegger sees himself continuing Kant’s project, particularly in Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics.