Hegelian Universalism and the Impossibility of Escape

Musings on Todd McGowan’s ‘Emancipation after Hegel’

I recall a conversation from a few years ago at a cafe in Olinda, a lovely highland town in the Greater Melbourne area of Victoria, Australia. The last place you’d expect to discuss Hegelian universalism. The details have now escaped me, except for the memory of the perfectly brewed coffee and the luscious jam-covered scones. I was reading a book by C. S. Lewis, which led to a lady—let’s call her Susan—probably in her sixties, asking me about it. She remembered her husband having Mere Christianity on his bookshelf and had always been charmed by Lewis but never got around to reading him. And this Lewisian lure led to us chatting about Christianity and God. Again, the cafe being the last place you’d expect to have a dialogue on theology and metaphysics, though I’m certain this wasn’t the first time C. S. Lewis caused strangers to opine on such esoteric matters. Susan’s congeniality made me disregard my dad’s advice that polite conversations should never involve religion or politics, so I kept prodding her for what she truly believed. Unlike periphrastic intellectuals, Susan got to the point and, in fact, candidly stated her beliefs. When I asked her about how one reconciles the fact that there are myriad religions worldwide, entirely contrary to the exclusive truths of Christianity, she nonchalantly replied, “There are many ways to heaven.” Tantamount to the notion of all religions being equally true, consciously or not, Susan doesn’t believe in the universalism of Christianity. I was perplexed.

Atheism is not antithetical to Christianity but immanent to its structure: to paraphrase Cadell Last, the truth of religion is Christianity, and the truth of Christianity is atheism. You can’t have one without the other. In Christ, God dies to himself, and humans are left to carry the burden of being; we become radically responsible for existence amidst the lack of a big Other, the stable background and guarantor through which reality makes sense to us, e.g., science, reason, democracy, so-called “Western values”, etc. As Hegel said it best, Christianity is the religion where the absolute irreconcilably debases itself: “The highest estrangement of the divine idea... is expressed: God has died, God himself is dead—is a monstrous, fearful representation, which brings before the imagination the deepest abyss of cleavage.”1 In this cleavage, in God’s act of kenosis (self-emptying), the ground of being leaves us the abyss of freedom to fully shoulder the responsibility of this precarious reality in the thick of its groundlessness. In freedom, the only way to become a Christian is through doubt, the doubt of an atheist, where one experiences the subjective destitution of Christ on the cross. And so, I view Susan’s pluralism favourably. I’d much rather prefer her type of Christian, or for that matter, Muslim, Buddhist, etc., than the perverse Bible-thumping fundamentalists we, for instance, see poisoning the American Republican party and facets of Australian politics. Yet, I can’t help but be baffled by the incongruity in Susan’s belief: it not only runs into myriad contradictions but, given she professes to be a Christian while admitting other religions are equally true, is absurd from the outset.

(I understand belief doesn’t function as a set of propositions one subscribes to in the Kripkean sense, i.e., “If a normal English speaker, on reflection, sincerely assents to ‘p,’ then he believes that p.” But for one to believe involves partaking in narratives, rituals and cultural norms where one is immersed in background practices that we aren’t even conscious of. We believe within a symbolic network involving other people and salient objects like religious artefacts (e.g., the bread used for the eucharist) or cultural ones (e.g., a driver’s licence signifying one is fit to drive when we know you really aren’t). Functionally, belief is decentralised. When you claim to believe, you believe through an irreducible alterity2, which itself lacks a locus of truth. Through an analytic philosophy lens, this phenomenon was perhaps best captured in Wittgenstein’s concept of a ‘language game.’3)

The Abrahamic religions, and Christianity in particular, claim to be exclusively true: “I am the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6) or “Thou shalt have no other gods before me” (Exodus 20:3). These verses point to Christianity being a non-pluralistic religion, where its truth is authoritative and self-justifying, and a believer must accept this datum. Kierkegaard saw in the paradox of belief4 that God is something thought cannot think; however, the believer grasping their ungraspability, assuming the paradox, is a necessary step for a Christian. In our ultimate concerns, the concerns that surpass no other and are constitutive of our being-hood outside of an instinctual animal, be it an ethico-political cause, falling in love, belief in God or lack thereof and the most centred acts of the human mind5, we cannot recourse to external events or a substantial reality, e.g., a philosophical system, scientific theories, the positive empiricism of economics or political science and the like—or Hegelianism in Kierkegaard’s case—we rather arrive at them retroactively.

To say one believes in a religious system—this also applies to scientism, democracy, capitalism, communism or anything structured like religion—is not the same as saying I carefully weighed out the evidence and reasoned my way to make the best choice, similar to how a consumer buys a smartphone from the countless options at Amazon.com but we justify our belief post hoc. One must first step into belief in order to see the truths of the object of belief après coup. Kierkegaard’s Christian doesn’t believe in the truth of Christianity because, weighed against all other religions, it gives the best reasons to believe, but one first believes in God and afterwards finds reasons to justify their belief. However, we shouldn’t err in thinking these reasons are false since they’re retroactively posited; far from it, as this is the only way to truly believe. Much like the discourses of Marxism and psychoanalysis, the truth of Christianity appears to us only after one becomes a Christian. One cannot understand the truth of the belief system from a God’s eye view—accordingly, as Žižek points out, a critique of such a system has to be done immanently, not objectively, but with subjective engagement. Is this why God had to become Man in Jesus Christ? In aeterno modo6, maybe God wasn’t Christian enough?

Be that as it may, the point of the digression is to explain my bewilderment at Susan’s flavour of belief, which is the modus operandi of all religious believers in modernity. In a liberal society, everyone has their private beliefs, knowing very well that people with antithetical worldviews exist. Pre-globalisation, apart from a few outliers, this wasn’t the case for the majority of societies. Belief was a social act. People took part in rituals and ceremonies and lived through them as absolute; religion was part of the public consciousness. The idea of it being a private affair would have seemed alien to them; every aspect of their lives, including familial roles and civic life down to their very survival, was structured by symbolic meanings laden with religio-cultural traditions. In Claude Lévi-Strauss’ The Savage Mind, the Lévi-Straussian analysis of totemism tells us that so-called primitive cultures had myths and totems not due to any innate sacredness to these artefacts but they were empty signifiers structuring people’s thoughts and experiences. The social edifice provided a framework for people’s belief, and, similar to Heidegger’s Dasein, belief is “out there” in the world. In a twist of irony, one could argue through the Lévi-Straussian structural anthropologist framework that modern people are more religious than the pre-moderns; by choosing to resign into their inner world, modern believers use spirituality to make sense of the incomprehensible and dizzying pluralism of being a global subject. Belief is deeply personalised, with quasi-Perennialist phrases being thrown around, such as “spiritual but not religious,” along with the rise of mindfulness practices and the corporatisation of Eastern spirituality. And so, since modern believers lack the social framework for their belief, they can’t allow a distance from believing by transposing it onto a cultural object. They are forced to substantiate belief within and carry the burden of being an authentic believer—Kierkegaard, in his despair, of course, is the quintessential embodiment of the predicament of modern religious belief. Along with social belief, the universalism of religion is dead.

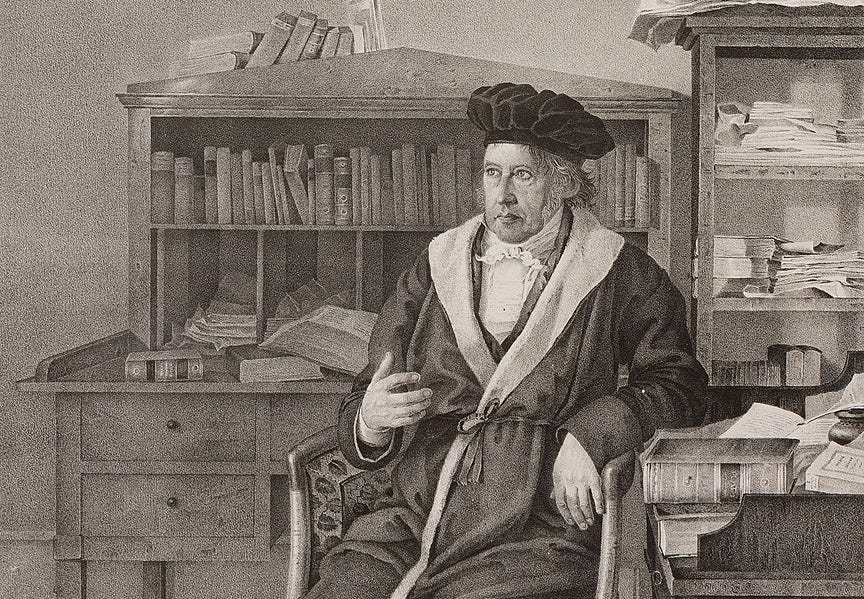

Perhaps a particularist perennialism is possible with the Baháʼí Faith, but a Christian runs into myriad problems if they reject universalism. There’s no escaping the universal in Christianity; one can’t parley with Christianity like 50 Cent’s Window Shopper, scrolling through all the available religions and picking and choosing what you like. Being a Christian is not adding another tool to your spiritual toolbox. The pronounced evangelism of Protestant Christianity (and, for that matter, Islam, too) is not an anomaly, but it’s in accord with the monotheistic doxa that its truths are exclusive and absolute. A believer shall have no other truths before the Truth. Indeed, much like the abolitionist movement in the West (e.g., the American and British Quakers) has subversive roots in Christianity, so does the violence of colonialism, where the “savage” had to be civilised by spreading the word of the gospel. As Terry Eagleton wrote in his review of Tom Holland’s Dominion, “Holland is surely right to argue that when we condemn the moral obscenities committed in the name of Christ, it is hard to do so without implicitly invoking his own teaching.”7 But these are remnants of the past. While thinkers such as Holland argue that secular liberal movements, e.g., feminism, LGBT+ rights, anti-racism, capitalism, socialism, etc., have Christian underpinnings, the West is not a Christian culture anymore. God, as we all know, thanks to an old German bloke with a resplendent moustache and a peculiar love of horses, is dead. But universalism, on the contrary, is more alive than ever.

In yet another twist of irony, as Adrian Johnston identified, we’re at a juncture: those who take themselves to be secular are religious and religious where they take themselves to be secular. Religious believers know their religion is not the only game in town, so by privatising their belief, they are, in effect, secular. Susan, for instance, doesn’t see Christianity as being true for every person and culture. On the other hand, a “tech bro” tycoon who probably proclaims to be an enlightened, rational atheist sees themselves wholly aligned with the universal; that is, Elon Musk and Peter Theil’s ilk see themselves as holding the answers to humanity’s predicaments. Startups, for instance, famously run like a cult, and the founder has semi-divine status, as seen in the rise of tech-sages from Mark Zuckerberg to venture capitalists like Naval Ravikant. Moreover, by becoming the handmaiden of capitalism, the ideology of technologies like AI has tentacles reaching every corner of the world, abetting the universality of capital, heedless of nation or culture. The universal of the technocapitalist—or, as per Yanis Varoufakis8, should we now say technofeudalist?—reaches and does violence to every particularity. Technocapitalism does not serve the needs of people, but we are instead engulfed by it where the logic of capital subsumes difference, be it religion, sexuality or tradition. Countless examples of local communities being devastated and withered away by corporate power could be enumerated; in fact, we are now immune to such stories as we’ve heard them ad nauseam. Even for those of us who don’t have it too bad along with our bullshit jobs9 that at least pay the bills and put a proverbial roof over our heads, the violence of capital ought to be analysed phenomenologically through burnout and tiredness that Byung-Chul Han10 theorised on poignantly. On analysis, we see problems that are labelled as mental pathologies are rather social ones and the result of subjectivity under the current psycho-social structure.

Universality then seems to be the source of absolute violence, where it eliminates particularity and, indeed, kills the subjects—for readers not familiar with theoretical jargon, that’s, in effect, you and I. No matter the content, be it religious fundamentalism, slavery, colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, scientism, or technologism, universalism ought to be the great enemy of any philosophy that deals with subjectivity. Does this mean we should reject universalism in itself and solely assert our particular identities as ontological givens?

Towering theorists like Judith Butler11 think so, and indeed, the current zeitgeist is to oppose any and all universals except for that of capital. Hegelians, however, reject the rejection of universalism. Namely, Todd McGowan (working through his fellow travellers like Slavoj Žižek and Catherine Malabou) believes the universal not only has a place for subjectivity, but there’s also an impossibility of escape.

One can’t act as an individual without recourse to a universal concept, be it religion, the state, science or a sociopolitical movement. Hegel himself thought the inability to escape the universal of society was obvious, which is probably why he spent a little time discussing Stoicism. In The Phenomenology of Spirit (PoS), despite the indomitable prevalence of Stoic thought in Western philosophy. He makes a short remark in Section B: Stoicism, Scepticism, and the Unhappy Consciousness of PoS that Stoic freedom is mere abstract freedom and not actual; in having empty freedom without content, Stoicism doesn’t make one truly free in the retreat into the self, detached from life. The Stoic, being passive, unengaged, and a world unto themself, can only think through what’s given to them by the very outer world they negate:

“The freedom of self-consciousness is indifferent to natural existence and has therefore let this equally go free: the reflection is a twofold one. Freedom in thought has only pure thought as its truth, a truth lacking the fullness of life. [...] Here the Notion as an abstraction cuts itself off from the multiplicity of things, and thus has no content in its own self but one that is given to it. [...] Stoicism, therefore, was perplexed when it was asked for what was called a ‘criterion of truth as such’, i.e. strictly speaking, for a content of thought itself. [...] This thinking consciousness as determined in the form of abstract freedom is thus only the incomplete negation of otherness. Withdrawn from existence only into itself, it has not there achieved its consummation as absolute negation of that existence.”12

We then ought not to downright reject universalism, which inevitably leads to relying on the universal for our particularity. Instead, we ought to strive towards finding a better emancipatory universal:

“One’s particular is never as particular as one imagines it to be. The subject always proclaims its particularity from a universal position, though this position often remains mystified.”13

Anarchists romanticise the individual. From Henry David Thoreau to the modern “Bitcoin bro,” the fantasy of anarchism is escapism. There’s a messiness to being human. If you give a dog food, shelter, and sex, the problem is solved, but give these to a human, and the problem begins. Having our needs met is the last thing we desire. Escaping this messiness, be it through nomadism or transhumanism, is seemingly easier than dealing with the human animal. One may love humanity in the abstract, but as Dostoevsky’s Father Zosima tells us in The Brothers Karamazov, in the particular, we’re smelly, may sneeze too loudly and, on occasion, have irrational outbursts. Humanity is an abstraction that doesn’t materially exist—nor does the individual; the human being exposes us to the unfathomable abyss of the other that abstractions never will. Dealing with this alien called a human remains elusive; escaping this burden, therefore, is seductive.

McGowan points out that public transport is an example of how everyone feels out of place. When on a public bus, one is faced with people from all backgrounds, classes, predispositions, and walks of life. In our self-interested act of using the bus for our need to get to a location, we’re confronted by people with whom we wouldn’t usually be associating. Such an encounter could be sanguine if you strike up a spontaneous conversation with someone that you find congenial. However, this mostly isn’t the case and facing the stranger’s alienness is traumatic; this is why people try their best to resign into the inner world, putting on headphones, reading a book, working on a laptop and using their private life to shield oneself from the outsider who is palpably close to them. The commuter desires to escape as the presence of the other is alienating, and we never truly know how to deal with the outsider—of course, we don’t know how to deal with ourselves either. Crypto-anarchists find fault with social institutions and claim they are oppressive—the state being the chief amongst them. Hence, the remedy is for individual freedom to be maximised. Freedom for them is being free of the burden of dealing with society with its concomitant disarray—at times, even ugliness—and overcoming the out-of-placeness, the alienating feeling the commuter experiences on public transport. Their escape is into the nirvana of freedom—although none of them knows what freedom entails and so unconsciously desire not to be free because to get the thing is the end of their fantasy. The insurmountable paradox of anarchism lies in the act of separating the self from society, requiring a society in the first place. They can’t actualise into the anarchist without a society to fight against. Rebellion requires something to rebel against, and the moment this dies, so does the rebel. Hegel would say to a libertarian-anarchist: “They pretend that what they are engaged in is something that is only for themselves and in which their sole aim is to bring themselves and their own essence to fulfilment. Yet while they act and thereby present themselves to the light of day, they immediately contradict by their deed their very pretence of wanting to shut out the daylight, to keep out universal consciousness, and to keep out everyone else’s participation.”14 No different to everything else in the universe the anarchist does not stand on their own. Akin to Stoicism anarchism, too, “focuses solely on what it negates and thereby gives the external world an absolute value. By focusing on how little his servitude concerns him, [the anarchist] inadvertently gives it significance. This mode of valuing contradicts what the [anarchist] claims about its own position.”15

In that vein, apocalyptic Christian fundamentalism and techno-anarchism are two sides of the same coin. Both eschatologies speak to the impregnable angst of being human. The fundamentalists believe our world of sin is corrupt; humans have plunged into their wickedness and await the second coming of Jesus Christ, who will right all wrongs, putting our anxieties to ease, and all of creation will be as God intended. The anarchist believes society is a boot on individual’s freedom who, if not for the power imposed on them, would live freely as intended by “human nature,” and so dismantling every institution that holds society together would let us live in unshackled freedom. Both worldviews are a fetishism of escaping into the future.

In attempting to overcome their alienation and asserting a particular identity, they inevitably do so against a universal: the theological one of Godless secularity for the fundamentalist and the political one of the state and society for the anarchist. And yet any particularist position that negates the universal, be it the political, epistemological or ontological, fails at particularising itself because even if individuals ostensibly act as if their self-interested aims are unto themselves, they end up betraying their actions:

“The problem is that it is not so easy to avoid the system. Hegel does not simply add the whole to the dialectical method. The whole is operative as soon as the method is. It is possible to assert particular difference, but one always does so through the articulation of universality, even though this universality is not often explicit. In his discussion of individuality in the Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel makes clear that it is impossible for an individual to act without reference to the universal. Without an investment in the universal, the individual would not act at all.”16

Take the typical case of the modern self-helper who strives to self-actualise and “be the best version of themselves” only to unconsciously become a slave to global capital as a consumer and worker. Yet, in perfect correspondence to the stoic, the self-helper too doesn’t have subjective freedom as they don’t confront their alienation by seeing themselves in relation to a universal, i.e., a society. Despite working in one’s self-interest with the illusion of acting as an independent being, they aren’t free because their inner lives are completely vacuous of thought. Freedom isn’t contingency but the ability to discern, employ one’s reason and choose as a rational animal—which the self-helper lacks. They think only through what’s given to them by the dominant ideology of the day, and so cannot be a free being because thinking, a negativity that cuts through reality, doesn’t exist as the self-helper is drowned in the excess positivity of a society that wants its subjects to be hyperactive; they are but a pawn in the social machine, deluding themselves into thinking they are free or are in pursuit of authentic freedom.

Hegel tells us that the only way for one to be free is through social freedom:

“One can imagine the subject pursuing its self-interest, but the problem is that this pursuit is not freedom. The subject’s interests—even up to its interest in its own survival-are given to it by the society and the natural world in which the subject emerges. Hence, as Hegel sees it, self-interest has nothing to do with the subject’s freedom, which depends on the subject alienating itself from the interests that society and nature have given it. The free subject alienates itself from its own givens, and the state is the vehicle for making this alienation explicit to the subject, which is why Hegel insists on it so decisively, in contrast to a loosely bound community, which would not reveal the subject’s alienation. It is only through identifying itself with the state or some parallel collective structure that the subject recognizes that its freedom does not lie in the pursuit of its self-interest but rather in the uprooting of that pursuit.”17

In fact, politically speaking, Todd McGowan contends that any leftist emancipatory project has to be universalist by definition, as a movement that tries to achieve unity through particularity, a nation, for instance, is ineluctably rightist as it always excludes the outsiders, i.e., those not in the nation. A complete nation is a pseudo-universal, much like an individual who professes to be at one with themselves.

We are self-conscious beings that live through the dialectic of the universal and particular. If not, it’s impossible for us to subjectivise. In seeing our necessary reference to the universal, “Hegel takes the further step of claiming that universals exist within a systematic totality that relates them to each other. One cannot make an isolated truth claim that does not bear on all other possible truth claims.”18

Herein lies the radicality of Hegelian logic, making him the paramount thinker of incompleteness. Hegel was not a formalist like Gottlob Frege or Bertrand Russell, who worked in the abstract (mostly mathematical and now computational) study of a priori propositions, rules of inferences and deductive arguments. However, borrowing from Aristotle and Descartes’s metaphysics, Hegel was interested in the logic of the whole, where the ostensible dualisms between the material and mental world could be overcome. As Frederick Beiser writes, Hegel “began the mature exposition of his system with logic; but he saw logic as an essentially metaphysical discipline, whose task is to determine the nature of being in itself, not merely formal laws of inference.”19 Formal logic would not allow contradictions, that is, F and ¬F cannot be both true, but Hegelian logic demonstrates that by following the law of non-contradiction in reality, we arrive at insurmountable contradictions where, vis-à-vis the whole, F and its inverse can be true as these aren’t part of two discrete realities. For instance, if we consider the famous Zeno’s paradoxes that much ink, particularly in mathematical logic, has been spilled over, a Hegelian would have no reservations when running into a paradox. Notwithstanding the (still contested) claim by some mathematicians that calculus, with its study of continuous change, has solved the paradox, Zeno’s arrow would indeed be motionless. As the paradox goes, [1] if time is composed of distinct, indivisible moments or “nows,” [2] if a flying arrow occupies a specific position in space at each of these moments, and [3] if motion requires the arrow to change position over time, but no such change occurs in any single instant, the paradox arises: how can the arrow ever move if it is stationary at every moment? During any given “now,” the arrow is simply “where it is” and takes no time to be there—or, in other words, it already is where it was supposed to go, making the motion of a flying arrow impossible. Moreover, formal logicians tend to be atomists (loosely speaking), that being, things are at one with themselves, all relations are external and “facts” of the world cannot be broken down any further—which is why holding onto paradoxes seems absurd. Even the most heterodox 20th-century analytic philosophers like Wittgenstein tacitly accepted the law of identity, ∀x (x = x), that is, X is X. But Hegel saw particularities, be it facts, objects or whatever that particular is, in the world can only exist in relation to each other conditioned on a universality—a universal in service of a particular; the moment we attempt to isolate them they cease to exist, as metaphysically, X is what X is not. Or, more dialectically put, if X were an identity, it would encompass its negation, too.

If we momentarily leave aside metaphysics and focus on our immediate and pure experience of a thing, we see how a thing is never solely itself. As I write these words, I have a cup of coffee next to me. It doesn’t take much thought to realise that the cup is not an independent object. Leaving aside the obvious mereological truism that the whole of the cup is made up of parts, the cup, taken as a thing on its own, exists in relation to the world. The cup sits on a coaster that’s on a table, appears to me as a vessel containing a hot dark brown liquid in contrast to other objects that are within my purview, has an ebony colour because sunlight shines through my window, etc., and to make a quasi-Heideggerian point the cup gets its “cup-ness” with relation to my subjectivity that reaches out to the world and exists within an intrasubjective symbolic network. I, as a subject, “is the immense-absolute-power of negativity, the power of introducing a gap or cut into the given-immediate substantial unity, the power of differentiating, of ‘abstracting,’ of tearing apart and treating as self-standing what in reality is part of an organic unity.”20

If not for subjectivity, this cup is dead matter; it’s nothing but a physical substance of atoms, quarks or whatever “the stuff” of the physical universe entails, but those defined properties are categories that emerged through interrelated conscious minds. In that vein, nature (if there is such a thing) is weak; nature is nothing. But I digress! The point being, even if we try to imagine an object existing independent of subjectivity, a pseudo-Kantian-thing-in-itself, that object can’t exist on its own footing but only in relation to the rest of the universe.

The appearance of an object tells us its essence is already split from itself, and Hegel goes a step further and shows how even our most direct experience of a thing—regardless of the aforementioned relations, be it subject-object or object-object—is still relationally mediated by a universal.

In PoS, the first form of consciousness is sense-certainty, which attempts to get at the knowledge of a thing, e.g., the coffee cup, without the mediation of thought, that being, all presumptions of the relational nature of things, mereology, conceptual abstractions and the like go out the door. Sense-certainty believes “I” circumvent thinking about the object and concretely know (or experience) the cup in its immediate essence. The coffee cup appears to my direct experience unadulterated by thought (which is what I did when reflecting on its essence); I encounter it in the here (within space) and now (within time), and no more has to be said. Doesn’t this seem like common sense? It’s saying I cognise something and therefore know a thing: I point at an object, I immediately apprehend it, and I gain concrete knowledge of the object I direct my attention towards. But this is the “natural” consciousness’s mistake. Sense-certainty fails; above all, Hegel holds that truth is unchanging and thereby shows how these common sensical notions are wrong. Accordingly, throughout §§ 101-108 in PoS, Hegel outlines the failure of trying to get the truth of an object without further qualifications or mediations. Let’s say that I point at the cup to cognise this object without conceptual specifications. Firstly, if I don’t have a concept of a cup, my pointing becomes nonsensical as all I’d have is billions of photons (and whatever else of the physical universe) hitting my senses, and that’ll be meaningless. Secondly, even with a concept, I only point at the cup through the mediation of abstract knowledge. When claiming, “This is a cup in the here and now,” it has to be an enduring claim if it were true. And yet, if the cup exists in the now and I want to gain concrete knowledge, I never do as time passes; the “Now” at my moment of pointing is a now that has been. Likewise, the “This” splits into two “Thises”: [1] the coffee cup as an object and [2] myself as a subjective “I” experiencing the coffee cup. And much like time, what occupies a place, too, is changing. The “Here” as an object is empty of content; it could be my coffee cup, keyboard or copy of The Phenomenology of Spirit. Unless conceptual thought, which is universal, mediates my apprehension of things and reveals to me the dialectic of the object, I have no way to gain true knowledge of my coffee cup. As a self-conscious being, there’s no escaping the universal, even in the presence of my most immediate experience. As Robert Stern writes, Hegel’s argument “is that even apprehension does not transcend the universal, for in apprehension we are just aware of the object as a ‘this’, which does not constitute the object’s distinctive particularity, but rather its most abstract and universal character.”21 Sense-certainty, on finally realising its failure, moves to perception, and that, too, fails. Indeed, the journey one goes through in reading the PoS is how all structures of consciousness lead to a contradiction (another term for failure) needing to move to a higher sublated level. Kant would keep these contradictions within the transcendental horizon, that is, a failure in our field of consciousness, but the Hegelian sleight of hand is to imminently demonstrate that these contradictions are not just in our epistemology but in reality itself.

Notwithstanding the violence of universalism22, we can’t escape it as it is through the universal we particularise. LGBTQ+ activism is perhaps an example of trying to create a movement bereft of universalism. The proper critique of the movement is not the rightist reactionary one that LGBTQ+ people are corrupting the social fabric; rather, the leftist critique ought to be that they aren’t corrupting society enough. Like all social movements, the LGBTQ+ struggle, too, has a multifaceted and nuanced history that cannot be defined through a singular framework, and so the following criticism is of the liberal strand of LGBTQ+ activism. Ironically, liberalism, which initially was what led to liberating gay and trans people, has also become the ideology behind their downfall (as seen from recent attacks on LGBTQ+ people by conservatives and the reactionary right). If LGBTQ+ people choose to stick to their particularity and claim the struggle for their rights is solely individual, it undermines the true emancipatory power of social justice. Particularist movements devolve into moralist spectacle, as we see with the spectacle of political correctness or the bizarre phenomena where an infinite number of arbitrary genders are conjured up as if identity were simply a performative game like picking out what clothes to wear for the day. Treating identity in such a cavalier manner is not only insulting to the struggles of LGBTQ+ people who’ve suffered greatly in their fight for emancipation but theoretically also leads to a Hegelian “spurious infinity” that’s an endless series of x + 1, e.g., 1,2,3,4… For Hegel, a true infinity has to be one that overcomes23, not an infinity that’s more of the same type. Similar to the natural numbers, an infinite series of gender identities, while they may have mathematical validity, is meaningless. Such abstract infinities aren’t experienced by us concretely, like the coffee cup I described earlier or any day-to-day experience, be it a mundane household object or the social world we relate to in our daily lives—it doesn’t take much reflection to realise that our relationship with a neighbour or a friend is qualitatively different to how we relate to mathematical objects like the set of cardinal numbers. Particularist gender identities become a pseudo-identity as the act of “collecting gender” parallel to the consumer “collecting commodities” has no change in how we relate to ourselves and the world. There is no “becoming,” no matter how many genders, sexualities, etc., one identifies with, as there’s no change in our subjectivity, and so it becomes an absurd project, indeed a spurious one.

(Perhaps it’s due to the false infinity of gender identities that Todd McGowan and Slavoj Žižek claim that in the acronym LGBTQ+, the “+” is the only true infinity. The “+” could be an identity of its own as it creates a shift in our subjectivity where we see the void at the core of our being and confront the universal alienation of all human beings irrespective of gender, race, sexuality, etc. Accordingly, the “+” is a universal signifier.)

Social movements that work through the universal (e.g., the civil rights movement, women’s suffrage, and recently the Iranian Mahsa Amini feminists protests) always expose how “the whole always has a hole, that no social whole can achieve a perfect self-identity in which every part has its proper place.”24 Subjectivity is engendered precisely through this failure to achieve wholeness. Our authentic existence is found not by positing identities ad infinitum but through confronting this hole in ourselves and reality. If we treat the whole (the universal) as yet another particular, we have no point of reference to understand our own particularity. On the contrary, acknowledging the existence of a universal and knowing we are inevitably in relation to it allows us to change it, not by circumvention, but by working through it. In this “working through,” we find true subjectivity, which is the incompleteness and contradiction that runs through us (Subject) and reality (Substance). Hegel “asserts a previously unheard-of division that runs through the (particular) subject as well as through the (universal) substantial order ‘collectivity,’ uniting the two? That is to say, what if the ‘reconciliation’ between the Particular and the Universal occurs precisely through the division that cuts across the two? [...] What if, for Hegel, the point, precisely, is to not ‘resolve’ antagonisms ‘in reality’, but simply to enact a parallax shift by means of which antagonisms are recognised’ as such’ and thereby perceived in their ‘positive’ role?”25

We’re back to where we started. Should we then conclude that Susan is a true “postmodernist”? Isn’t her type of religion, pluralist pragmatism par excellence, similar to that of Jordan Peterson, who claims truth is “whatever that works,” with no regard to truth as such? From what I recall, Susan was apolitical; I presume due to her affability, she believed in common decency (an underrated virtue) as her politics. But isn’t Susan’s flavour of pragmatism what Peterson, too, follows?—in his case, though, this same logic has led him to reactionary right-wing politics. If truth amounted to practical application, Peterson’s diatribes against trans people, so-called “radical woke leftists,” the “Postmodern neo-Marxists,” or whatever terms he’s conjured up recently are justified within his particular logic. He may use Jungian-Darwinism to give his claims a semblance of metaphysical substantiality, but when all is said and done, he is a bona fide relativist. For the Petersonian, the truth of a claim doesn’t matter as long as it maintains social wholeness, i.e., sustains Western civilisation. Anything that’s “poisoning our blood”—to use a remark by Donald Trump—is antithetical to the truth. Accordingly, one should not be surprised that Peterson’s in bed with Elon Musk, Peter Thiel and the Tech-neo-fascists. They, too, follow Yarvinian26 accelerationist pragmatism that claims liberal democracy has failed, and we’re in need of a neo-Mornachist system with a CEO at the top running a nation like a startup. In contrast to Susan, however, an underlying cynicism runs through Peterson and the Yarvinians. The former’s particularism is the liberal kind, where she still believes the truth of all worldviews, even different from her own, but the latter kind does not, nor do they care for its verity. In fact, they do not rationally believe even in their own position, except brutally positing it as “what works” as an expedient tactic of pragmatism. Indeed, Peterson and the tech coterie are the true postmodernists. The Haitian pet-eating scandal peddled by Trump and Vance, for instance, isn’t pathological because it’s empirically untrue—meaning, it’s a falsifiable claim that’s been debunked—but rather because it uncovers the desires of those making the claim, e.g., anti-migrant xenophobia, creating social distrust for political expediency, scapegoating, etc. To reappropriate a Lacanian-Žižekian notion, one can’t escape unconscious ideological desires by looking at reality objectively and seeing Haitians for who they really are; if this were the case the moment the story was proven to be false, its peddlers would let it go. Rather, one only breaks the power of ideology not through escape but by “[confronting] the Real of our desire which announces itself”27 in our actions. Our ideological hold has nothing to do with empirical facts, as we’re already caught up in the reality we’re trying to objectively observe. Meaning: even if verifiable evidence of a Haitian person eating cats or dogs were found, anti-Haitian racism would still be wrong; ergo, simply “acting on the facts” is still a pathology. As the Lacanian quip goes, concerning “the pathologically jealous husband [...] even if all the facts he quotes in support of his jealousy are true, even if his wife really is sleeping around with other men, this does not change one bit the fact that his jealousy is a pathological, paranoid construction.”28 The aforementioned right-wing postmodernists refuse to see how their rational pragmatism is laden with ideology29. Or, more aptly, they know it, yet they act as if they don’t. Those who follow American politics closely saw JD Vance downright admit he made up the Haitians eating pets story; liberals were up in arms about his brazen admission but failed to see his logic of scapegoating, like Jordan Peterson, is perfectly internally consistent. Here, we see the unlikely marriage between Butlerian liberalism and the rightist cynics through their shared elevation of the particular.

So what’s after the aforementioned postmodern cynicism? Universalism, as I’ve argued, is politically the only way towards emancipation and, philosophically, the proper way to speak of truth. But what does the concept of the universal look like? Unfortunately, a universal that doesn’t violate one’s particular subjectivity has been few and far between. It’s rare because in thinking dialectically of ostensible differences between the universal and particular or, in other words, singularity and the whole, we shouldn’t exalt one over the other: “The irony of Hegel’s philosophy—an irony many have missed—is that, though he seems to serve up individuals for the sake of the systematic whole, the whole exists for the sake of singularity.”30 A true universal cannot exist if it doesn’t give way to the particular—not the particularity where you’re lost in the abyss of your self-relating negativity; instead, the universal proper that lets us “not have” together. As we’ve typically seen in politics, religion and sub-cultures like self-help, universalism cannot impose values, but it can allow particularity only by exposing the imminent failures in all social structures. The moment a worldview posits positive values, it stops being a true universal and becomes a particular instead. It creates an outsider and draws a line between the included and excluded. When you say something is good, you necessarily say everything outside is bad, even if you aren’t explicit. There is no neutral middle: what seems like the middle is always skewed towards a side within a predefined logic. Politically, this means that the only universal is that of collective struggle towards emancipation, never mind how those particular struggles are actualised, be it the Palestinian liberation, Iranian feminist revolutions, or the exploited working classes in the US, Australia and the developed world. Culturally, we see slips of this universal appear mostly in humour where the contradictions of our times appear unadulterated—this also is why people despise it when comedians start becoming moralistic. Religion complicates things, as it, by definition, speaks of matters that are of ultimate concern for us and of the infinite through the finite. Christianity, especially that of St Paul, is a religion that perhaps has come closest to a true universal, but it also fails the moment it becomes evangelistic.

(I ought to mention Peter Rollins’s Pyrotheology here: a project attempting to work through the true universal of seeing God not as the absolute that holds all of being intact but that which signifies the ontological lack in reality. Rollins is the rare person I’ve come across who’s attempting to create a praxis out of Christian Atheist philosophy. None of us—including himself—know where this project would go, but I’d contend he’s working along the same tradition of Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation, and so Pyrotheology is immanent to Christianity, not antithetical to it like Richard Dawkins-style New Atheism which posits it’s own big Other.)

The answer to Susan then is that she is indeed right about religious pluralism, but she’s right precisely in how wrong she is. Religion, regardless of how it concretely manifests in the world, will always be universal, not because all religions are true or lead to God but because they all inevitably fail to deliver. The promise of religion, be it eternal life, nirvana, or an ineffable spiritual bliss, is nothing but one that’s meant to be broken. The failure, though, doesn’t make religion false; instead, the universal truth lies in the very failure; failure is where religion appears in its truest form. When every social structure and mode of consciousness fails, we’re confronted with the truth we all share: the truth of shared non-belonging. None of us ever feel at home anywhere, and we know the promises of religion will never actualise and yet in this very non-actualisation, religion lives on. And perhaps this “subjective destitution” is an existential necessity; we realise our alienation and become subjects only in seeing how even God, the absolute—the domain that religion works within—necessarily fails to fulfil us and has not got the answers; we’re left with an insurmountable lack. But isn’t this where love enters the picture? Isn’t this where one realises our incompleteness can only be dealt with through one another? When we embrace the others’ alienation, don’t we learn to embrace our own, too? Isn’t this communion?

In the neo-Western Wind River (2017), Cory Lambert (Jeremy Renner), a Wildlife Service Agent, discovers the frozen body of 18-year-old Natalie Hanson (Kelsey Asbille) of the Northern Arapaho tribe in the Wind River Indian Reservation. On discovering the body, a search for the murderer begins as it’s clear it was a homicide. We also learn Cory himself lost his daughter, Emily, three years earlier, similar to how Natalie died, and the case remains unsolved. Natalie’s father, Martin Hanson (Gil Birmingham), and Cory are old friends; the families have known each other since their children were born. Eventually, we see through a flashback that Natalie was murdered by workers at a nearby oil drilling site. Cory promises Martin to avenge his daughter's death, and after a bloody confrontation, he does so. Cory kills all of the men responsible for the homicide after finding out it was the workers. Afterwards, Cory visits Martin to let him know the job is done as promised and that all the men have been avenged. When he goes to their home, he sees Martin seated in the garden, staring into the sunset with his face painted with seemingly indigenous tribal patterns. He asks, “What’s with the paint?” It’s his “death face,” Martin claims. Cory prods him further on how he knows of this tradition since all his ancestors are dead. Martin says, “I don’t. Just made it up, cause there’s no one left to teach me.” The film ends with the two men, one a white American and the other a native American, looking over the mountain range, both estranged from tradition and culture, sharing grief over the deaths of their daughters. This is the moment of universalism. Irrespective of their culture, they both experience loss and alienation as a constitutive part of their lives. This is the human condition. Together, they embrace that which is unbearable to bear alone: a universal we can’t escape nor would want to.

.

My conversation with Prof Todd McGowan:

G. W. F. Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion, vol. 3: The Consummate Religion, ed. Peter C. Hodgson, trans. R. F. Brown, P. C. Hodgson, and J. M. Stewart (Oxford: Clarendon, 2007), 125 (translation modified).

Mackie, Carolyn J. “Believing For Me: Žižek, Interpassivity, and Christian Experience.” (paper for ICS 2400AC W13, IDS: What Is This Thing Called Religion? Spiritual Difference, Secular Critique, and Human Maturity, ICS Faculty - Dr. Nik Ansell, Dr. Doug Blomberg, Dr. Shannon Hoff, Dr. Bob Sweetman, Institute for Christian Studies, May 2, 2013).

Read Hipólito, ., & Hesp, C. (2022, July 1). On religious practices as multiscale active inference: Certainties emerging from recurrent interactions within and across individuals and groups. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/t9632.

“The supreme paradox of all thought is the attempt to discover something that thought cannot think. This passion is at bottom present in all thinking, even in the thinking of the individual, in so far as in thinking he participates in something transcending himself. But habit dulls our sensibilities, and prevents us from perceiving it.” Johannes Climacus, Kierkegaard, S. et al. (1962) Philosophical fragments, or, a fragment of philosophy. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Tillich, P. (2011) Dynamics of Faith. United States: HarperCollins.

Kierkegaard, S., Hannay, A. and Eremita, V. (1992) Either. London: Penguin Books, p. 54-55.

Eagleton, T. (2019) Dominion by Tom Holland review – the legacy of Christianity, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/nov/21/dominion-making-western-mind-tom-holland-review (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

Varoufakis, Y. (2024) Technofeudalism. Random House UK.

Graeber, D. (2019) Bullshit jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Han, B.-C. (2020) The Burnout Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Butler, J. (2000) Contingency, hegemony, Universality. London: Verso.

Hegel, G.W.F. (1977) Phenomenology of spirit. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 122.

McGowan, T. (2021) Emancipation after Hegel: Achieving a contradictory revolution. New York: Columbia University Press, p. 185.

Hegel, G.W.F. and Pinkard, T.P. (2018) The Phenomenology of Spirit. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 240-241.

McGowan, T. (2021) Emancipation after Hegel, p. 20.

Ibid., p. 180.

Ibid., p. 203.

Ibid., p. 183.

Beiser, Frederick C. (2005). Hegel. Routledge.

Johnston, A. (2018) A new German idealism: Hegel, žižek, and dialectical materialism. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, p. 138.

Stern, R. (2013) The Routledge Guidebook to Hegel’s phenomenology of spirit. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, p. 61.

The wrong universalism, however, like nationalism or liberalism, that creates the outsider will certainly do real violence. But that, too, is because it’s a pseudo-universalism, which really is a surreptitious particularism.

Rose, O.G. (2022) ‘True Infinity’ Overcomes, Medium. Available at: https://o-g-rose-writing.medium.com/true-infinity-overcomes-e00563d0fa2 (Accessed: 15 September 2024).

McGowan, T. (2021) Emancipation after Hegel, p. 186.

Žižek, S. (2008) The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso, p. xvii -xviii.

Curtis Yarvin (influenced by Nick Land) is the anti-egalitarian and anti-democratic theorist behind the Dark Enlightenment, which has seduced many in tech-billionaire circles and even up to the 2024 presidential election VP nominee and challenged doughnut buyer JD Vance. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtis_Yarvin.

Žižek, S. (2008) The Sublime Object of Ideology, p. 48.

Ibid., p. 49.

“For neoliberalism, ideology is often implicit and indirect, and thus requires no explicit and direct ideological enforcement. Individuals who believe they are following their own free determination are in fact operating within the confines of an ideological system that has already predetermined the logic of their motion. Thus, instead of establishing a political ideology and seeking conversion, the frame of our universal existence is already converted to the logic, in this case, the logic of an inhuman spectre of capital that continues to self-revolutionise itself independent of whether or not humans would like it to continue or not.” Last, C. (2023) Systems and Subjects: Foundations of Philosophy and Science. Philosophy Portal.

McGowan, T. (2021) Emancipation after Hegel, p. 188.

This was great. Yk as an American, I really think Zizek describes our Protestant theology of abandonment. Where the New World never really had a Big Other.

really liked the piece.