Common sense is not so common is a saying used in conversations spanning from public transport etiquette to office politics. Apocryphally attributed to Voltaire, the bon mot works because common sense is supposed to be a truistic understanding to most of us, regardless of our backgrounds or proclivities. The truth of a statement, as it were, becomes abundantly clear when we look at its meaning through our everyday use of language; ergo, there’s no need for any further philosophical analysis. Politicians, following this lead, have begun to sell themselves to the public as candidates who have a common-sense policy agenda undergirded by an ordinary sense that anyone can discuss over the kitchen table—notwithstanding that, it’s getting harder for people to afford kitchen tables anymore. Be that grief as it may, in times of institutional distrust, post-truth, lack of a symbolic epicentre that meaningfully holds our world intact, and God most likely being dead, it seems common sense is the only fortification against our existential groundlessness.

Philosophers—G.E. Moore being chief among them—have likewise affirmed common sense as an insurmountable epistemic tool for overcoming long-standing philosophical problems, e.g., realism vs. idealism or the proof of an external world. Moore’s argument, contra 20th-century scepticism and British idealism, is strikingly simple, yet he defends it fastidiously in his 1939 essay Proof of an External World: It goes (1) here are my hands; (2) it is a fact that there are at least two external objects in the world; (3) ergo, an external world exists (Moore, 1993). He qualifies criteria for a ‘proof’ are: (1) the premises adduced as proof for the conclusion must be distinct from each other; (2) a premise cannot be a belief but has to be something you know to be the case; and (3) the conclusion ought to directly follow from the premises. For (1), Moore adumbrates that the evidence is self-evident. When he claimed, “Here are my hands,” he knew at the time of enunciation that the hands he was waving around existed in the world, bar none. Based on this conclusion, one can ascertain that a world outside one’s mind exists. In fact, it seems offensive to our everyday reasoning and lived experience to claim otherwise concerning such commonsensical matters. If we can’t conclusively assert such Moorean propositions, e.g., ‘Here is a hand’ or ‘I am currently seated on a rather uncomfortable chair as I type these words on my keyboard,’ then we will never have sufficient proof or evidence for anything whatsoever. Moreover, although 20th-century analytic philosophy seldom touches on phenomenological existentialism, without such background certainties, we can’t even exist in the world. Much of our conscious life is lived with the certainty that truisms like ‘The Earth existed before I was born’ or ‘I have a body’ are unequivocally true. Moore, in turn, argues that this class of propositions is proof enough for myriad philosophical contentions, as we are more justified in believing them over other premises used, for example, those in a sceptical argument. That being said, Moore (2010) does admit to a peculiarity in such ‘Common Sense view of the world’ propositions: If we know a proposition belongs to this class, then by definition, it is true, and to say otherwise—namely, claiming ‘I know something to be commonsensical, but it is not true’—is self-contradictory. We may claim, for instance, ‘I know democracy is the best form of government, yet this is not true,’ and it is logically consistent, but this cannot be the case for a commonsensical claim.

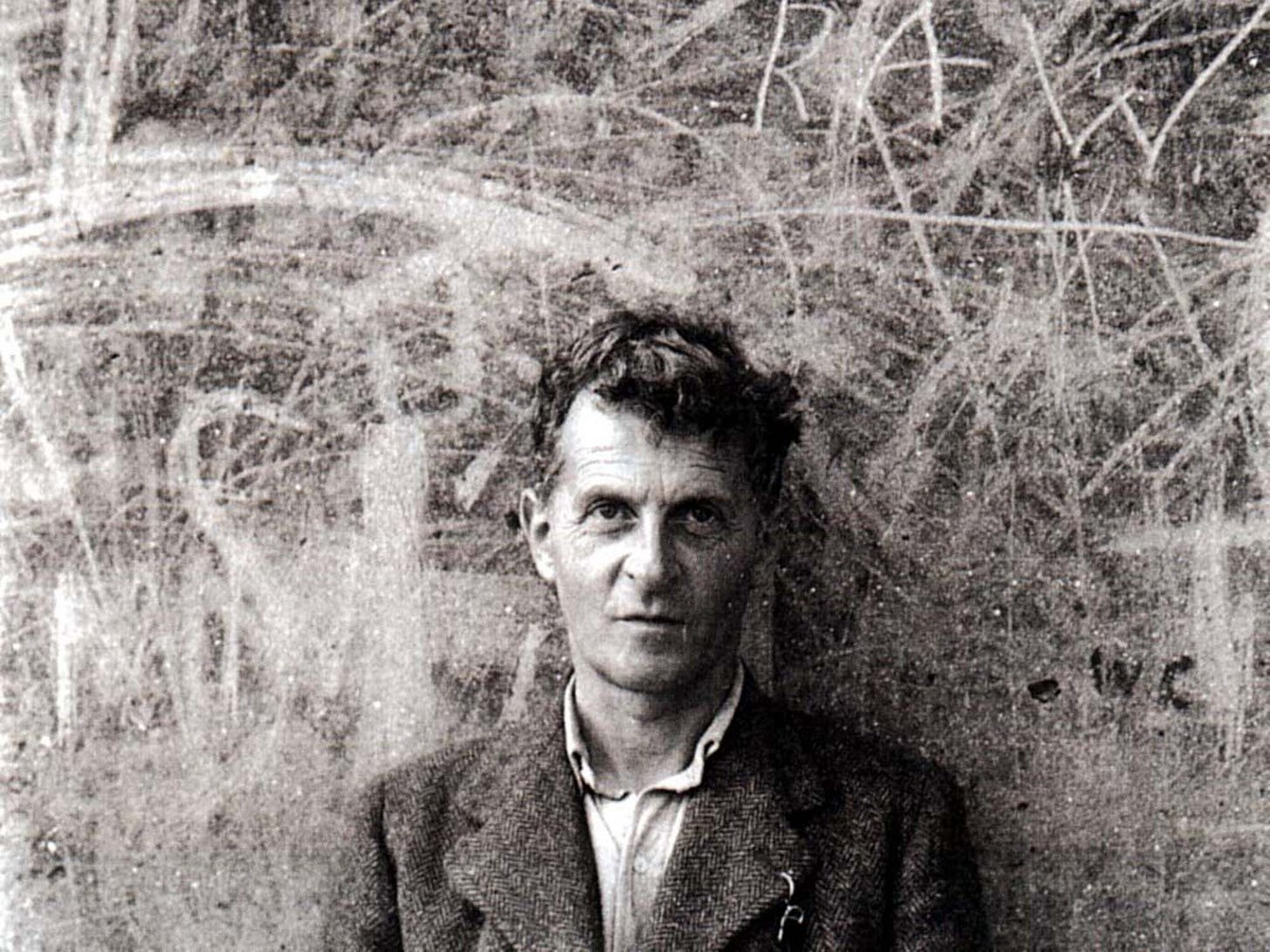

Ludwig Wittgenstein introduces hinge propositions, a form of background, albeit non-philosophical, understanding upon which our whole network of knowledge rests. Analogous to hinges on a door, if we want it to stay put and function, i.e., open and close, the hinges must be fixed, or at least the fixity must be presupposed. Wittgenstein (2003, §94, p. 251) writes in his unpublished notes, On Certainty (OC), that such an edifice is “the inherited background against which I distinguish between true and false.” How, in this case, are Wittgensteinian hinges different from Moorean certainties? A helpful way I’ve found to delineate this difference is to read Wittgenstein as what Badiou (2011) called an anti-philosophical philosopher, akin to the modus operandi of Nietzsche, Marx and Freud. Meaning, these peculiar hinges aren’t philosophically analysable. While Moore would attempt to demonstrate he has proof for his certainty about a commonsensical state of affairs in the world (e.g., he attempts to empirically demonstrate the existence of his hand), Wittgenstein makes no epistemic commitment to prove hinge propositions nor to their ontological verity—in that regard perhaps it’s misleading to call them propositions. They are already part of the language-game, as Potter (2020, pp. 413-414) outlined, a ‘form of life’ we’re embedded within that expresses datums about ethics, religion, aesthetics, or any culturally situated practice, and indeed structures our commonsense. However, Wittgenstein is not a romantic philosopher either. What we know by following the rules of a language game isn’t irrational but, as Hipólito & Hesp (2023, pp. 179–198) argue, an embodied form of rationality that holds epistemic validity in itself. Wittgenstein would defend the forms of life and Moorean certainties against scepticism, not because they provide fixed points of philosophical truth, i.e., they are subject to change yet are necessary, but in a given language-game if a sceptic “tried to doubt everything you would not get as far as doubting anything. The game of doubting itself presupposes certainty” (OC, §115, p. 251).

Will relativism then be the logical outcome of such ordinary language philosophy? If the truth of a proposition is found only within the context of an epistemically unjustifiable background against which it’s asserted, we’re led to a type of Gödelian paradox (Nagel & Newman, 2001): The system we use to discern between true and false is neither provable on its own terms nor shown to be consistent; ergo, “the difficulty is to realise the groundlessness of our believing [or knowing]” (OC, §166, p. 252). Does this mean there’s no epistemic toolkit we can elevate to find certainty in our knowledge? In this respect, an enlightenment thinker or a logical positivist would defend the methodology of science with its empiricism and rigorous formalism as the bulwark against relativising knowledge. But can science be given such salience? Is there something unique in the scientific method that tells us truths about the world in contrast to other epistemologies, e.g., religion or mysticism? Needless to say, answering these questions is beyond the scope of this essay; however, I will attempt to provide prospective answers by analysing Vasso Kindi’s Wittgenstein and Philosophy of Science (Kindi et al., 2017).

I will discuss the late Wittgenstein, as this was the thinker who wrote what came to be known posthumously as the Blue and Brown Books, Philosophical Investigations (PI) and On Certainty, whose concepts and theories I briefly covered. More importantly, this was the philosopher who introduced a radical cleavage into analytic philosophy, rendering the philosophy of science a form of sociology, so to speak. That being said, I ought to mention the well-known historical fact that the early Wittgenstein of the Tractatus was a paramount influence on the founding logical positivists of the famous Vienna Circle in the 1920s, the group that, both through its proponents and objectors, gave rise to the philosophy of science as a discipline. Wittgenstein was no stranger to the logical syntax of science and scientific empiricism. Like them, it’s clear that he respected science yet eventually distanced himself from the group due to their philosophical militancy, or, one might say, scientism, as Monk (1991) highlights. In her chapter for Wiley-Blackwell’s A Companion to Wittgenstein (2017), Kindi presents four major figures in the post-logical positivist historical turn in philosophy of science who are closest to and influenced by the Wittgenstein of PI and OC: Stephen Toulmin, N.R. Hanson, Thomas Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend. Respectively, they introduced the notions of scientific activity as multifaceted—lacking a single common feature but akin to a sport defined by a network of similarities and dissimilarities between activities (Toulmin, 1961); the theory-ladenness of scientific observations (Hanson, 1958); paradigm shifts (Kuhn, 2012); and the contextual theory of meaning (Feyerabend, 1962). Regardless of the specificities and technical differences, all of them would reject an analytical formulaic methodology of science, where scientists learn abstract definitions adhering to a set of rules constituting a quasi-Platonistic scientific method. In other words, science is not algorithmic; ergo, it cannot be programmed into a Turing machine but has an organic social epistemology. Is science then still stuck in a type of Wittgensteinian metaphysical constructivism? I argue not.

I will use examples from quantum mechanics and consciousness studies to illustrate my argument, fields that have garnered unparalleled interest within and outside academia. Theorising on them has indeed become à la mode, leading to a lucrative online content industry, and this isn’t arbitrary. While the motivations for research in the fields differ, both can be categorised as what Thomas Kuhn would call crisis science. In contrast, Godfrey-Smith (2021, pp. 104-113) outlines that Kuhnian normal science is done within a well-established framework where researchers broadly agree on the foundations, what problems to investigate and how to approach them within a given time and paradigm, e.g., Newtonian physics and molecular genetics based on DNA and RNA, it’s no different to scientists solving a puzzle with predefined rules. This cannot be said for fields in crisis that have reached a critical mass of anomalies. Maudlin (2022, p. 2), for instance, has stated that while the General Theory of Relativity is precise on its own terms and there aren’t any foundational debates among physicists, the same cannot be said for quantum theory and “instead, there is raging controversy.” Likewise, David Chalmers famously coined the term ‘hard problem of consciousness’ to capture the difficulty in developing a fundamental theory to explain qualia and subjective experience (Chalmers, 1997; Feiten, 2025). And, in my opinion, in past decades, no scientists or philosophers worth their salt have claimed they have a satisfactory paradigm-creating theory of consciousness, even if they’ve criticised Chalmers’ thesis.

Extraneous factors did not cause a crisis in these fields. QM emerged through developments in thermodynamics, the photoelectric effect, wave-particle duality, and other areas of 20th-century physics. Similarly, investigations into modern consciousness have taken place within psychology and neuroscience from their inception and after Noam Chomsky’s 1950s linguistics revolution in cognitive science and artificial intelligence. N.B.: Matters become complicated in the study of consciousness, as the term is used liberally across disciplines and—given the nature of its subject—cannot be entirely empirically and mathematically driven. Regardless of their internal workings, it’s normal science: Researchers were following the rules and practices of the prevailing paradigm that gave rise to a crisis. Feiten (2025) argues that as a field develops and adheres to its own logic, it ends up undermining the very foundations that allowed the field to function in the first place, leading to a dialectic, then ipso facto, a crisis, as the field can no longer operate with the previous presuppositions. A Kuhnian paradigm could effectively be a Wittgensteinian language-game; however, unlike other kinds of games, the scientific one goes deeply awry; the game immanently malfunctions, which imbues a revolution and eventual adoption of a new game—amusingly, Kuhn notes in Structure, this is when scientists become interested in philosophy. Karl Popper was right to say a permanent openness characterises science, but the openness isn’t at the level of an individual scientist’s attitude—in fact, this would be antithetical to common sense—rather, the enterprise functions only through failure. I.e., the incompleteness of science in which every paradigm inevitably fails leads to an appearance of openness despite not being essential to the scientific process.

A critic may object that this argument about the language-game of science can be made about every other game. They are correct. But the epistemic conditions science contingently created in our culture have now become necessary in the myriad language-games we’re embedded within—as Johnston (2019, pp. 74-128) illustrates in detail, contingency always presents itself as a necessity. In other words, there’s no going back to a pre-scientific epistemology because if a hypothesis isn’t analysed scientifically—albeit through its current paradigm, which we know isn’t the final one—it might as well be nonsense. The same cannot be said for a language-game like Christianity. In that regard, for us, the truths of science do have a higher salience than those of a religion. Of course, this does not mean every hypothesis is scientific; for instance, the arguments in this essay aren’t scientific, but if I am to develop my thesis further, I ought to analyse this piece through a variety of scientific tools and demonstrate why it isn’t so. In contrast, I believe it’s self-explanatory why I should not have to do the same for Christianity, though it may have been a different case if I were writing this essay in 15th-century medieval Europe.

…

Dear Reader,

This was a minor essay I wrote for an epistemology unit in my master’s degree. And so I hope you forgive me for using technical jargon without the warranted exposition—this is a pet peeve of mine when writing philosophy. I wrote this piece for an audience familiar with Moore’s and Wittgenstein’s work, plus I had to strive for brevity. The arguments I’ve introduced have been fleshed out in detail in original sources, and I recommend you read them for some of the best philosophy written in the past century. Moreover, please feel free to leave any thoughts or questions in the comments, as I would love to discuss them.

References

Moore, G.E. and Baldwin, T. (1993) ‘Proof of an External World’, in G.E. Moore: Selected writings. London: Routledge.

Moore, G.E. (2010) ‘A Defence of Common Sense’, in Philosophical Papers. Routledge.

Wittgenstein, L. and Luper, S. (2003) ‘25. On Certainty’, in Essential Knowledge: Readings in Epistemology. Longman.

Badiou, A. (2011) Wittgensteins Anti-Philosophy. London: Verso.

Potter, M.D. (2020) The Rise of Analytic Philosophy, 1879–1930: From Frege to Ramsey. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Hipólito, I., Hesp, C. (2023). On religious practices as multi-scale active inference: Certainties emerging from recurrent interactions within and across individuals and groups. In R. Vinten (Ed.). Wittgenstein and the Cognitive Science of Religion: Interpreting Human Nature and the Mind (pp. 179–198). London: Bloomsbury Academic. Retrieved April 18, 2025, from http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350329386.0018

Nagel, E. and Newman, J.R. (2001) Gödel’s Proof. United States: NYU Press.

Kindi, V., Glock, H.-J. and Hyman, J. (2017) ‘Wittgenstein and Philosophy of Science’, in A Companion to Wittgenstein. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 587–602.

Monk, R. (1991) Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. London, etc.: Penguin Books.

Toulmin, S.E. (1961). Foresight and Understanding. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Hanson, N.R. (1958). Patterns of Discovery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kuhn, T.S. (2012) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions: 50th Anniversary Edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Original publication 1962.)

Feyerabend, P. (1962). Explanation, Reduction and Empiricism. Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 3, 28–97.

Godfrey-Smith, P. (2021) Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science, Second Edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Maudlin, T. (2022) Philosophy of Physics: Quantum Theory. Princeton, Boston, Massachusetts: Princeton University Press.

Chalmers, D.J. (1997) The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford University Press.

Dialectical Science and Why AI Research Needs Continental Philosophy (2025). Available at: RSam Podcast #70 (Accessed: 2025).

Johnston, A. (2019) A New German Idealism: Hegel, Žižek, and Dialectical Materialism. New York: Columbia University Press.